A black wrought iron fence above the exit from the underground garage connected a high-rise to the last townhouse in the Old Park creating a chute that turned back toward a carport. More high-rises stepped away to the south on the west side, and townhome apartments circled the park to the east. The end unit was empty. The five young men had specifically chosen this spot for their roundup, their crime against nature. They were city kids about to kill a goose. Waving their arms, three of them pushed the flock toward the exit gate, where they thought they could corner one of the birds, two guys outside the gate ready to wrangle it to its doom. Not that easy discovered the boys. The geese were quick, and the men’s hearts were faint when it came time to hammer one, knock it senseless, with the bats and clubs they wielded. The guy from Jersey came through with a neck grab, a whirlwind roundabout, a broken neck, just like they do in the country. They fled in cars to a house nearby, where they plucked and cleaned the goose. None of them felt bad for the bird — the grounds guy had for weeks been daily plowing goose shit off the sidewalks with a tractor. The migrant population was out of control. He brought home the liver and his wife made pâté. They returned to the house the next day with girls and wives, and cooked the bird. The hunting party enjoyed a royal repast of their prey. How different from the kill by the son of the apartment complex owner who had shot a deer up in the hills, driving there in his VW bug — the owner then told the men he employed to drag it out for the kid, and clean it. The maintenance boss and his oldest employee took care of the kill. The deer hung outside the grounds equipment stall in the underground garage, below the Old Park, where the older fella drained, gutted, skinned it. The kill by the owner’s son, not quite the Deer Hunter, was licensed and ordered. The goose roundup by the young guys on the maintenance crew was reckless and rogue.

You’d think I hadn’t gone to college (there would be more to come). A few of my coworkers were studying engineering and two were working towards their certification in HVAC in their spare time, but all the guys at the apartment complex were working maintenance, unskilled labor — painting walls, declogging drains, mowing grass, vacuuming pools, shampooing or laying carpet. Working with their hands and sometimes their heads. I had temped as a seasonal at the Denver Botanic Gardens, liked the outdoor working life, and so applied to maintain the grounds: mowing, raking, shoveling snow. The big boss reportedly said I wouldn’t stay for long, since I was educated, but the supervisor told him I had passed the owner’s personality test with flying colors. Mr. Owner had to go with the data, conservative businessman that he was.

My mother had spent a year in college before she married her first husband. Her oldest daughter had spent a year in college before she married her first husband. After mom married my father, who adopted her daughters, then skipped town not long after my birth, she put most of her hopes in me, le bon fils, I was to be educated, she worked that into my head. I graduated as a College Scholar, and she and that oldest daughter both attended the commencement. For them, I cut my hair short for the first time in college. My girlfriend took me to a brand new Vidal Sassoon salon in Chicago. All my professors promoted graduate school as the next step, but I resisted in light of my indecision as to a career. My degree in American Civilization crossed disciplines; I was too curious to focus on specifics when connections could be made between the tenets of civilization. I wanted the big picture: the roots and old growth and suckers of the giving tree. I subsequently drove a cab, pounded spikes for the Colorado and Southern, tended bar, programmed computers, apprenticed as a taxidermist, opted for gardening. I wanted to know and be all Americans, all the souls that Walt Whitman catalogued and toasted in Leaves of Grass. My mother and sisters wondered what I was doing.

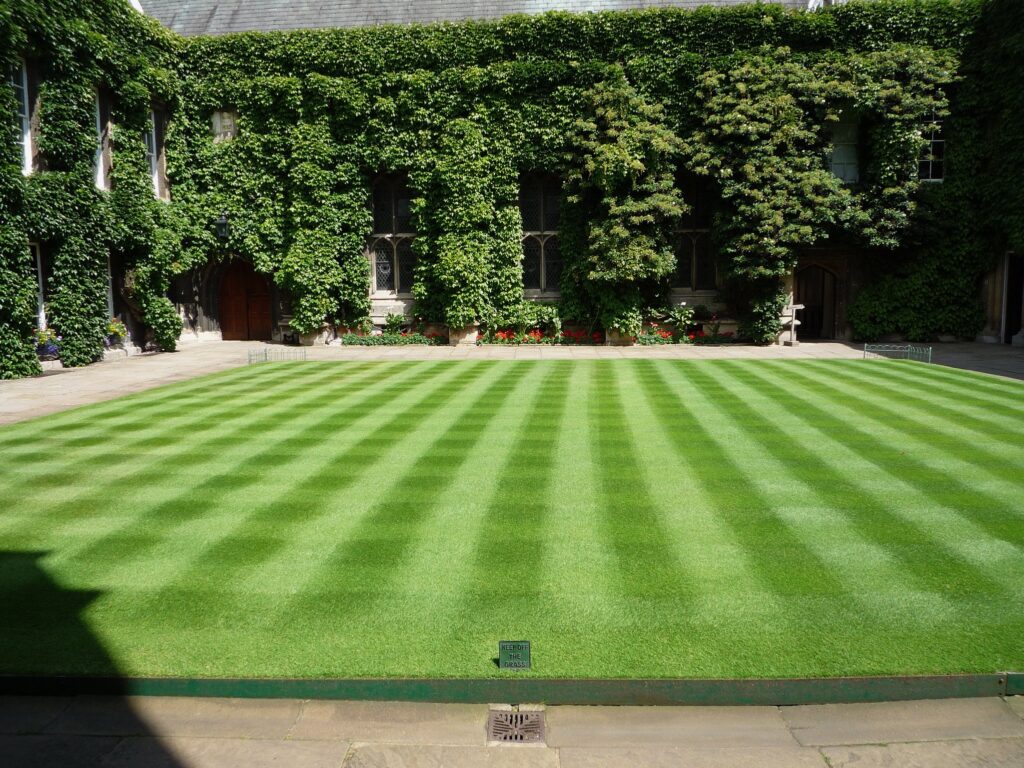

Dark glasses all day long I donned, mowing acres of turf, trimming shrubs, checking and repairing sprinklers, sweeping carports, plowing and shoveling snow. Working with my hands, learning trades my absentee father failed to teach me. Being a native of this land and tilling the soil for sustenance felt good. Once I mastered the dirtball skills of maintenance, I took up gardening and design. Free rein of the gardens I was given, and learned about annuals and perennials from former colleagues at the botanic gardens. I roamed city parks in summer to see what flowers the Denver Parks staff designed and planted. I kept notebooks of arrangements featuring hyacinths and lilies, purple salvia, dusty miller, petunias, geraniums, and zinnia, all categorized according to their textural depth, ranges of height, and color fields. I mapped every planting bed in the complex, and studied soil types and sun angles to create dazzling displays, revered by long time residents of the complex as the best flower gardens in Denver.

Design got to me, as it practically interwove the trades and art: not only did I learn soil chemistry, water demands and sun requirements for plants, I painted texture and color and foreground and back with perennials and annuals and vegetables. I created lunar landscapes, Martian drifts of dried weeds and fake flowers in hanging beds above an indoor pool; planted a vegetable garden that included ornamental kale, chili peppers, purple okra, colorful maize, and mock strawberries. People were delighted. I thrilled to plant exotic displays of castor beans and flowering tobacco. I was dependable, hard working, intelligent; regardless, my boss sometimes wondered what I was doing. Was I naïve to think that this could amount to a career?

There were two many Mikes working maintenance, so they called me by my first name John. I never answered to it, had never used the titular name of my father, and so the other maintenance guys thought me a space case. I was as gone to them as my father was to me. I didn’t just wear the dark glasses during the day, outside in the sun, but nighttime, too. I had worn them all through college. My way of avoiding contact, limiting insight by strangers. For a while during my days as a gardener, I wore no glasses at all, having broken my pink old-school owlish frames of dark green lenses. I wondered what I was doing, living on Capitol Hill blurring the pavements and street trees ala the Impressionists my old school mates so loved. City life was busy enough without the overload of a million details. I was keyed to the pulse, the vibe of the city where I had grown up. I’d rather walk blind.

I was a Yardbird clucking for feed, music and drink, and an apartment to house my stereo and records, orange lawn chair, pink floral couch, postered bed, standing vintage Philco radio, and FiestaWare served at a small grey dinette table and chairs. This stark inventory doesn’t differ much from the one I litanied after my mother had a stroke, moved first to the hospital and then a nursing home, and my sisters and their daughters and I divvied up her furnishings — I was at my beginning, my mother near her end:

shower curtains Marylyn

hamper Norine

seahorse plaques

gold leaves wall decoration

grocery buggy

vacuum, broom, mop M’s daughter

ironing board N’s youngest

card table and 4 chairs E’s daughter

metal shelf unit

dishware, clay pot Eileen

linens

3 lawn chairs and table

bell and wood ornament

3 glass nesting tables Norine

plant stand

TV – $150

2 orange chairs — $25 each

easy chair

cabinets, étagère Norine

couch hide-a-bed — $150

5×7 rug — $50

marble table

(quilted foot rest) and 2 bedroom stools

2 pole lamps Eileen

clocks

3 old paintings, 1 landscape, kitchen paintings

2 table lamps Eileen and Norine

kitchen table and 4 chairs

microwave, blender, toaster

roosters, ceramic duck and cat

painted German plates, Dutch figurines Marylyn and Norine

bed, bureau, nightstand

wardrobe, mirrored stand

Grandmother’s bracelets, 3 rings

“Mike” is not listed, since I took nothing besides a box of costume jewelry and a charcoal drawing by one of her aunts, of a horse standing near a cowboy collapsed in the snow near a graveyard marker. Eileen got the less morose companion piece portraying a lone paddler on a desolate wooded river — both nicely framed with burnished gold leaves of carved wood, corralling that aunt’s dark imaginings.

What was I doing? I had apprenticed as a computer programmer in Chicago at the best training ground around, and when I was laid off thanks to a buyout and slimming down of the insurance company where I worked, I refused an offer from the American Medical Association to work in their computer division. I had had enough of suited corporate office work, denying myself the hedge of becoming a tech upstart. I used my severance pay to attend Bartending School, and managed a neighborhood restaurant near Racine and Webster, but the Chicago clouds and humidity left me longing for sunny days and dry heat. When I returned to Denver, I worked the Denver Botanic Gardens as a temp, and wanted to continue working outside. Was it the big corner yard where I grew up in North Denver; was it my years of delivering papers on the bike through summer and winter, unconsciously absorbing the extremes of elements and seasons; or the summers of bicycling telegrams around the city; or the yearly trips across the Midwest to first see relatives and then attend college, seeing the growth of the interstate system after having become versed in the blue highways of Nebraska and Iowa? I worked for a lawn service in college, worked for a summer at DBG, and sailed through the personality test, so got the yardbird job despite my dark glasses and quiet attitude. I didn’t have a plan, just flow like a river, skiffing over the shallows and pools.

By the time I delivered the eulogy for Ezzard the goose, the people around the complex knew I was a different bird, per the Trashmen: “A-well-a ev’rybody’s heard about the bird/B-b-b-bird, b-birdd’s a word.” I had become the grounds supervisor, having taken the plantings to a level unparalleled in Denver for apartment dwellers. The complex had some of the highest rents in the city, and the tenants expected exquisite upkeep. Early stars of the Denver Nuggets like David Thompson called the complex home. The owner had run for the state legislature, and was now a city councilman. I played a hard game of racquetball on the apartment courts and soaked in the sauna with the moneyed renters. My wife and I spent many a night at the Rainbow Music Hall. We were part of the music scene, the downtown scene, when people were fleeing the inner city, when punk was born. Early in high school I had seen The Yardbirds live at Hal “Baby” Moore’s hall in Aurora. Always on the lookout for music and gestalt beyond the high plains. I visited the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx in pursuit of a working internship, but our finances would have been too tight. I started designing and installing landscapes for friends in my spare time. Then Ezzard died, and we held a mock funeral in honor of the old goose. The ceremony rivaled Saturday Night Live for its sardony. The job never got better than my after hours turn as Jonathan Edwards preaching to the congregation…

WELCOME FRIENDS, to this solemn occasion. I expect that those in attendance knew Ezzard, but for the sake of this eulogy, I want to recount some of the major events in this Blessed Mother Goose’s life. The first time I met this bird, she was named Egbert, and to this day it is unclear whether that was the more appropriate signature; but Ezzard to us she shall remain. To many renters at our fair apartment complex, this Mother Goose was an awful apparition on their daily walks. But this one-eyed Jack-of-a-Goose took guard of the goslings abandoned by their honky mothers. She did defecate like other geese, favoring the sidewalk, and oh how I was tempted to plow her under, but instead we took mercy and tried to save her after her scrap with a hound. To Harvey’s Bird Paradise we took her, and then to Friend Iggy’s pigeon coop for a needed rest, but a kidney infection took its toll, and we bade this fair fowl goodbye, soon to be joined by Fred the swan, her everyday nemesis in life. Yes, in both cases, mercy killings, but I say it be a matter of justice, for everyone lays out in his own mind how he shall avoid damnation, and flatters himself that he contrives well for himself, but trusts to nothing but a shadow. For a shadow of Ezzard looms over us, a regular Goose Gossage on the mound, and she’ll strike you down like she pushed old Klein into the lake. And so, Max Klein, as you offended her infinitely more than ever a stubborn rebel did his prince, it is nothing but her beak that holds you from falling into the lake again and again and again.

RATHER THAN bandy about her name, let us acknowledge Good Mother Goose Ezzard as the Revelator of Crestmoor Downs. Now, thank God, we have no ducks and but a few geese who pay homage to her. Let he who is without sin cast the first firecracker at these pilgrims, and let us never forget dear Ezzard, or ye shall perish by the wrench and hammer.

AMEN

Kenny drove the green John Deere at forward in the parade. Ward followed in a white golf cart, a plastic goose astride a coffin like trunk straddled across its bed. Ralph, who had broken his wrist using a hole saw drill, followed cast held high heralding another plastic white goose driving a yellow utility three-wheel scooter; behind him two women wearing black veils sat side-saddle on the black upholstered seat above the toolbox. Other women in black processed behind, with the Super who wore a fur vest crutching his way up the rear, nursing a broken limb. The pallbearers dressed in blue and red plaid sport coats and industry ball caps out of respect to the revered goose, hoisted the coffin into the shop. Candy, Evie, and Madge, the front office woman force, began beating pans. Ralph and the Super raised the plastic geese in a gauntlet, welcoming the preacher from the sanctity of the highrise into the shop. He would deliver the eulogy. He wore a two-tone grey sharkskin suit, white shirt, and blue silk scarf stole. Behind his dark green highway patrolman specs, the assembled could not see the tears that Ezzard’s testament stole from his eyes. The trunk had been opened to display a previously frozen bird — who was to say it wasn’t the deceased? Tenants who lived in the highrise above the parking lot watched the funeral march into the maintenance shop wondering what the staff was doing. Those were our days of wine and roses.

Early on in his field as a dirtball at the apartment complex, he grew a mustache like nearly everyone else working there. Players on the Oakland Athletics during their heyday of World Series’ victories in the 1970s sported mustaches as their signature, marketed by Charlie Finley, the owner of the club. The look spread across the faces of American males — it had to do with the West as well, the pictures of the Marlboro Man saturating an addictive society. SNL comics showed up with lip hair, and nearly all his fellow workers took the look on. Only a few pictures remain of him with that brow above his lip, with his curly hair and glasses looking like a hip Groucho Marx. It didn’t last long. He decided if he were letting his facial hair grow, he would only do it during the winter to provide an extra layer of warmth as he toiled in the snow and cold. If he wasn’t shaving, he wasn’t going to spend extra time trimming a ‘stache or beard, so his cold weather beard grew down his neck too. The beard served him well during the winter of 1982, when a big blizzard hit Denver.

Trying to plow and shovel and salt the exit ramp out of the underground garage near Building A in the Old Park (where the earlier goose gauntlet had gone down) the crew recognized the heft of the Christmas Eve storm as they cleared the ramp only to begin again. Soon the maintenance guys from the buildings were directed to clear the other ramps, precarious slopes when covered in snow. The building managers who only worked outside their doors in emergencies started shoveling the entrances, breezeways between buildings, and the sidewalks around the highrises. His in-laws had arrived a few days prior for their first Christmas with his two-year old son. He had to go home, and got a ride with the old German who lived in Littleton, the fella who skinned the deer had a huge family to attend. Most of the crew stayed on through the night. This arrangement set his routine for all of Christmas week.

He hitchhiked to work early each day, right after the sun rose. Drivers gladly picked him up, since everyone wanted someone to help push them if they got stuck in the two feet of snow that had fallen over that day and long night that arrived on the dregs of the winter solstice. The sky shone blue on Christmas, the city buried in white, the temperature below freezing. People didn’t realize the severity of the snowfall in those first days. Denverites expected the sun to melt the snow so they could get back to their lives. He would celebrate the holiday when he got home that evening, and each evening of each day he worked.

Everyday, he plowed the snow with the John Deere, usually after he had shoveled a pilot trail through the drifts. They had tried a broom, tried a blower, but the heavy drifts left no other choice. Though he insisted on walking across the acres of grass in summer to detect leaking sprinklers, and because what else was the grass for but to play games, no one else knew the curve of the park walks, so he was the best man in light of the grass and sprinklers that would otherwise be torn up by an errant blade. He took a short break for lunch, usually eating from one of the casseroles or sandwiches made by the kind residents. At the end of the day, he swallowed a few shots of the Christmas booze donated to the maintenance guys before he hitched home to be with his family. Most of the crew slept in empty apartments during the day, and took over on the trucks and plows at night, clearing the streets and the straight walks along the curbs. This went on for eight days. Some residents experiencing cabin fever left in their cars, thinking city streets would be as clear of snow as streets that crisscrossed the complex. They would get stuck just fifty feet down the boulevard, and the supervisor would have to tow them back to the shelter of the complex. What did they think they were doing?

The owner’s other son who worked in the office, not the lawyer son who bagged the deer, lost his Christmas money while he was plowing. He thought it fell out of his pocket when he got out of the truck to check the snow blade. For the next several months, the crew paid close attention to the clean up of the snow in the vicinity of where the son was plowing. No one ever admitted to finding the cash. This son had attended the tail end of the service for Ezzard. He looked like a Mormon missionary alongside the sauvecito guise of the preacher. Money versus smarts and style.

Long before the holiday season was upon him, his mother and sisters had requested a list. This year, he had suggested they return to the long litany of practical items and fantastic notions that he had compiled for them a few years prior; let them pedal their minds around his earlier pedantics. As it was, no one was exchanging presents this year, at least for a week, since the storm had cancelled the Christmas morning breakfast in Mom’s apartment….

Mother tells me everyone wants a List. A good two weeks ago, Sears or Wards, one or the other catalog store, announced a pre-Christmas closeout sale: order from the old catalog now, before the prices go up for Christmas, they seemed to be saying. I’ve found over the last two years that the department stores have advertised their after-Christmas sales the full last week before Christmas. That is the time to shop, if you’re willing to risk your hand and buy just what’s available, or what pops into your head. The big budget items that get all the TV spots and banner ads in the newspaper won’t be available five shopping days till Christmas. The keeping-up-with-the-Jones’ avaricious consumer cravings sell out.

Instead, count on your imagination. This doesn’t apply to folks who must forward gifts to faraway lands, to friends and family who won’t be home for the holidays. Nor does this apply to my family, for they must have a List in hand by Halloween. So Mom, Sis, Sis, and Sis, here’s mine:

a Black and Decker workmate, the cheap ($45) model, to use as a shelf with its own built-in bookends, or as a plant stand, or as a natural wood countertop for the chrome commercial meat slicer I asked for last year;

a rip cord chain saw, gas powered, so I could cut my own firewood, and pay for the saw in energy saved through one season;

a suit from Sheplers Western Wear;

the entire series of wildlife lapel pins, tie tacks, that were available at Miller Stockmen stores last Christmas — why, the Big Mouth Bass Club already boasts members in Boulder, Denver, and NYC, and I see no reason for not starting a Wild Pheasant Club but for the lack of pins;

a weekend in Tulsa, round trip by bus, if only to find out why Gene Pitney ever considered going there;

a $10 gift certificate to the downtown Woolworths;

a brand new Checker sedan, and a garage to park it in;

a carriage house above the aforementioned garage, rent in exchange for gardening work;

a system of streets safely given over to bicycle use;

regular street sweeping by the city of Denver of its bikeways;

a pair of Chippewa work boots, in black leather with oil-resistant soles and an everlast shine;

a pair of cowboy boots, ankle height;

a cowboy shirt, a rich midnight blue color with white satin ribbing, and pearl buttons;

a Krups coffee pot, pictured some time back in Esquire magazine, with a pot that doubles as a thermos;

a Pomco razor, the one with the slanted edge, for twin blade comfort in a single edge tool;

a case of Guinness Beer, forever warm;

a gallery opening for my no nonsense painter friend David;

an old fur for my hippie girlfriend;

a complete edition of Henry James, the Modern Library volumes that each contain an introduction by Leon Edel;

a couple of sweatshirts, muted colors, from Gart Brothers;

a mint condition, or brand new mohair buttoned cardigan sweater;

a Denver punk and new wave show at Mammoth Gardens featuring Patti Smith, Pere Ubu, and Talking Heads;

World Series highlights on Monday nights instead of football;

Major League baseball in Denver, with either a season ticket or TV coverage attached;

two new pair of straight leg Levi cords, any colors you choose;

a nice white shirt, 15 ½ x 34, with an understated collar;

the razing of the D&F Tower, or spotlights placed on it, as is, in memory of old Denver, from the Shirley Savoy to the RKO and Denham theaters, and the Five and Dime near the Daniels and Fisher tower;

an end to the Middle-East crisis and gasoline lines.

Perhaps I sound a bit too far-flung, but I’m certain that some of the items mentioned will meet your fancy. If you can’t get the Krups, buy the Norelco Espresso; if not the cords, buy Wrangler blue jeans. If no one can decide, I’d be more than pleased if everyone in the family pitched in and bought me a Nikon camera to fiddle with.

He let them know that Mom had gotten him the Pomco razor; everything else was still a go, except for the old fur for his girlfriend — she had become his wife and had retired her furs because of the controversy over animal hunting for trophies. One of the residents at the apartment complex was divorced from Denver’s biggest furrier — I told you it was high class. My family continued to wonder what I was doing, even after I had bought a house with my future wife, even after having a kid. Now my in-laws are in town, my sisters and mother won’t get to see them because of the storm, and my dealer friend is crashing between houses in our garden level apartment with his crazy wife and daughter, while two feet of snow keeps everyone holed up unless they’re out shoveling. Our white domestic duck named Duxter waddles around the little pond, carving out an igloo for himself. I hitchhike commute to work every day; I hitch home every night, retreat downstairs to shower and do a snort, climb the stairs to greet everyone, and drink a Tanqueray martini to reach a level of comfort through the family confabs over dinner. What did I think I was doing? My life was stretching beyond its means. I couldn’t afford to buy drugs. My wife complained of my low wages. I was approaching the status of native son that so many of my smart friends were exploring — writers, poets, painters living on the fringe. Most of the dolts from high school and my college roomie were getting business degrees. Not for me. The river flushed me into the delta of design, and I was paddling through uncharted rapids, doing what I could to avoid the sinkholes.

They were a motley crew who celebrated his departure for graduate school. He wore his characteristic black t-shirt, this one advertising the “New York Central System Road to the Future” red and white seersucker shorts, new Velcro sneaks and short bike socks on his feet, the dark highway patrol glasses shielding his eyes. His permed Olivia Newton John looking wife attended the picnic, his godson nephew, too, who was now taking care of the outdoor pool at the complex. The owner and his wife stopped by to say goodbye, and they ceremoniously handed him a scrapbook of memories, photos of his days working the grounds, claiming the soil, growing a savannah of grass with copses of trees, beds of perennial flowers, annual displays. He winced at the attention, but he was moving on, to an alternative degree program at a hands-on landscape design school in Massachusetts. Through savings, his wife afforded him the chance to get a graduate degree in a year’s time away from home, where he could devote all his energy to expanding his knowledge of design on the land. He would be doing it!

The Super, Ralph, Ward, Eric, JT, Tim, Kenny, Jerry, and Patrick were all there. They were some of the jamooks that I worked with, partied with, lived by during the late 1970s, early 80s. Danny had returned to New Orleans, the Denver life too cool for his warm Southern roots. He would arrive at the shop every Monday morning recounting the latest Mr. Bill episode on SNL, laughing about Bill’s predicaments. We all went camping up in Arapahoe National Forest one summer night, half of us smoking dope or dropping acid, cooking out, laughing loud and hardy, until we were nearly out of wood, and a few of the guys accompanied Danny up the road in his little truck, only to return in twenty minutes dragging a dead tree, fodder for fuel, well past midnight. Campers in the vicinity were not nearly as amused as we were. Bob had gone back to Jersey. No matter how much he practiced racquetball, I always whooped him, mostly due to my gangly reach. We cavorted down at Confluence Park when it first opened, swimming in the polluted stream of Cherry Creek and the Platte, scarcely noticing the filth if there was any, doing MDA without a care. The first grounds super, my cohort when I started, had left to start his own business. Mark had taken me winter camping along Lost Creek — I caught a cold as we hiked in across the iced over stream late one Friday in December. The next day when he and his buddy went hiking, I stayed behind in the tent, a fever sparking hallucinations all day, living Smilla’s Sense of Snow life, a whiter shade of pale. I would never do that again.

Ralph from Commerce City and a habitué of the Mile High Flea was one of the crew still working when I moved on. He was always buying cars and moving motorcycles. Friend Iggy turned us on to prize pigeons at a show at the Jeffco Fairgrounds, and he shared a Sheltie litter with us when our son was three — Macy became our son’s protective companion, alongside Duxter. Eric had an English mother, lived in Aurora divorced and alone, and more than enjoyed dipping those steel tentacles into the game pit of stuffed animals at the bar he frequented. He asked if STP on my cap, a punk platitude wearing those industry caps, stood for Stupid Tall Person. I always laughed about that. JT actually rented a cottage from us on our compound property; he went on to get a degree in engineering. The Super inspected our house before we bought it. He visited it a few times, and was dutifully confounded as to why we would buy a fifty-year old river rock house with two smaller bungalows on a large overgrown lot next to a factory. He was building a new house for his family near Southwest Plaza, a place he could board and raise horses, a suburban foothold on the front range surrounded by space.

I was naïve to think that college had introduced me to the spectrum of humankind Students came from countries around the world, as well as most of the states, and Chicago’s west side, but they were there to be educated, although sports or sanctity might have been the pull. This troupe of comrades from the apartment complex was a different sort, working men aiming for success, wanting to buy a house, financing a better car to drive, grabbing some fun on the side. Me, I was homesteading in the urban core, riding my bike, going to concerts for kicks. Different priorities, but camaraderie we shared. Was I a blue-collar poseur? Did I work for the working classes or just absorb their merit? It was my idea of a training ground in Americana. It would be naïve to think that I could call myself a native before I got to know a crew of working stiffs. Now that I knew them, and I had learned a lot from them, I could get back to the books. I could live, not stifle. Now I had a better idea of what I was doing, though most of these guys probably still thought I was a Stupid Tall Person. STP or Yardbird, you call it for this decade of my late twenties, early thirties. I was Chasin’ the Bird like Charlie Parker for fast trills and cheap thrills. Had a better idea but still not sure what I was doing. Grabbed my dunnage and filled the odd seat in the raft of design school sluicin’ through uncharted rapids. Bang a gong, get it on.