I’ve been going by the old manse for thirty odd years. Once when we toured the Lumber Baron Inn in the early ‘90s, my wife and I walked the block to where I grew up and saw an older man on the porch. I introduced myself and the missus, we talked a bit about the place and the neighborhood, but he failed to invite us in. I heard yesterday from the current owner that the old man and his woman lived alone, and finally sold it in 2002, when both were near 80 years old. I suppose they had a right to their suspicions, you never can know what people are after, but I kicked myself for not being ingratiating enough to warrant an inside peek. As it is, I’m currently sitting on a petition from a fella in our neighborhood to include the house we’ve lived in for near forty years to open it to a tour next fall — we did this once before, in the 1980s, when we were considering selling the compound of our house and two rentals, mostly because we were offended by our industrial neighbors. I’m not sure that my wife wants strangers traipsing through the place now. Regardless, I met the owner of the house where I was born and grew up, yesterday, as I bicycled by after a tour up the Platte and Clear Creek, doubling back through town as I’m want to do. I heard hammering and stopped to see a woman building a chicken coop in her side yard. I could imagine the sounds around the old farmhouse when it was built. Casually I rode up, told her the grounds looked great, that we had a big property that I tended, and “oh, by the way, I grew up in your house.” She stopped dead driving nails, and asked me my name, and said she had stopped to see her old place in Oklahoma, and would I like to step in. I thought I was hallucinating, what a welcome, and of course I said yes. It was 4/20 — here was the portal to my dreams.

I park my Soma Stanyon in the back yard, where the flagstone patio my brothers-in-law installed as a first attempt at home improvements should have been, but Julie let me call her said they had removed it the year before and poured concrete stamped in a block design — she showed me where they moved the slate to the west side of the house. I mentioned that my mother had bought the place for 13K, and sold it 20 years later for the same price, but she had sold off the lot to the north where an old garage stood so someone could build a small ‘50s era brick ranch, which was recently torn down, and the property has flipped hands a few times, so Julie didn’t know what to expect next on that site. After selling the lot and building a small garage to the east of the old house, my mother made what was left of the back yard into a flagstone patio and a dog run, which wasn’t particularly pleasant. We walked around to the front door, and Julie ushered me in.

The front bedroom had become her husband’s office; he’s a physical therapist. This was the bedroom with a picture window, which always impressed me as absurd, since nobody wants a huge plate glass window imposing the outside world on their bedstead, but that must have been a change made to the parlor before my mother converted it to a bedroom, so that the upstairs could be rented out. All three of my sisters occupied it at one time or another, with Marylyn and Eileen making the first pair, until Marylyn got married and Norine joined Eileen in the room with a fireplace, albeit ceremonial it was, tiled and grated. The girls had light blue curtains and green floral drapes. When I eventually moved in, the color scheme turned to a more manly brown and rust, with orange curtains, like my favorite Dobie Gillis shirt. The room no longer impressed me as huge — instead, it seemed small, and the closet was gone. The fireplace brick was exposed. It had assumed the appearance of a den, more along the lines of the parlor it once was. I gasped in silence at the change, and the scale. I imagine my old desk doing an arabesque with my standup bureau, and the closet where I shuffle and organize on shelves and in drawers my sweaters and pants to this day in my dreams.

Next I encountered the living room, which could be called cozy by today’s standards. So many new houses are open ceilinged, lodge height, and I remember this room as comfortable for all the times that my family rearranged it — that was something we did in the 1950s, move the furniture around every year or so for new ambience — with another picture window but appropriate for the room, and a side window to the west. The south and west light increased the breadth of the room. It had a couch that I hacked with a hatchet before my sister Marylyn’s wedding reception December 28 — so close to Christmas; was she pregnant or were they taking advantage of the holiday break? I didn’t know, but a kid brother 15 years her junior who worshipped her might have sensed something. My other two sisters had to sit through the reception on the cleave in the couch, taking turns covering the gash. I also knocked over a Christmas tree in this room and blamed it on the dog — that was another year, not her wedding time. Having a white-flocked tree displayed our modernist, sophisticated tendencies. My youngest sister Norine’s best friend from across the street visited and asked if we always kept our tree on the ground. It was probably a long needled pine to accept the flocking so not much damage was done after it softly fell to the floor. The present day room was nice but I was having a difficult time reckoning my thoughts about how big it once seemed. I would clean house for my mother when she worked on Saturday mornings, every other week. I recall dusting end tables near the couch, Windexing the picture of my grandmother whom I always assumed was my great Aunt Helen, since I knew her, not realizing the photo was of my grandmother. My mother may have told me once who it was, but later admitted her mother looked a lot like Helen. Now, there hardly seemed room for end tables. Are people too big, was I too small, do people not read in natural light? I remember a floor lamp in the dark corner of the room between windows, otherwise there was a table and lamp opposite it.

From the dining room I have a photograph of me at the head of the table on one of my teen birthdays, from high school, where I was known for never having a hair out of place on my soche haircut. We weren’t rich but I went to Catholic prep school on scholarship. There’s the claw foot long dining table, floral upholstered stiff back chairs, a credenza that held table cloths and cloth napkins below a grand mirror in a beveled green mirror frame that made the room look twice as big. I recall my sisters and their husbands sitting at the table. A mahogany cabinet opposite the credenza displayed the china and glasses, and drawers below held a modest library, mostly Thomas Costain books. The guys would make the crystal glasses ring by rimming them with a moistened finger. In the picture, my head looked small to me, which I could never reconcile with my hat size of 7 and a quarter. I guess I’m a big guy with what my wife calls a pinhead, but that’s when I get my hair cut short. The size of my head and face now impress me as large, due to age, the kind of big noggin a lot of old guys get. The room looks nice enough now with a modest dining table at its center. Julie asks if I remember some pocket doors between the living and dining rooms. I don’t recall those, we would have always had them open, but I think back to the small phone table in the corner of the room, dark mahogany like the rest of the furniture, where I answered a boy asking for my sister that she wasn’t home, so Marylyn instructed me from the living room, and when he asked when she would be back, I casually asked her “When will you be back?” without covering the speaker. Another time I picked up the phone to hear two classmates in seventh grade talking to each other, two girls chatting. Somehow I had been plugged into their conversation. We had party lines shared by households, but this was a rare coincidence, which should have introduced me to the cares of girls my age, but I learned little, instead mesmerized by how my eavesdropping was happening. The message was the machine.

The biggest change made to my family dwelling was the elimination of a wall separating a staircase to the second floor from an outside door into the dining room. Glass doors with white diaphanous curtains screened the door and entrance, before stairs rose to the upstairs rooms behind the dining room wall. My mother rented the rooms as an apartment, for income, specifically to soldiers settling in Denver after World War II. She met my father as a tenant. They were together for five years, until right after I was born, at which time he skipped town, fled to the Springs and beyond. I never knew him. She rented the upstairs to a nice couple as I was growing up; the woman, Georgia, would take me to Sloan’s Lake to feed the ducks. Another couple with two kids lived there later. I would play with the daughter and son twirling them around like big time wrestlers, never slamming them to the ground but going through the motions. Eventually my sister Norine and her husband Jim moved upstairs, and from the start it seems they had hard times. I recall Jim at times stumbling home after Norine had waited for hours. Besides her daughter, Norine’s only comfort was her Siberian husky, which chewed the baseboard on the staircase rising to the second level, as well as destroying the rosebushes my mother grew in the small back yard, besides two peonies. The apartment stood empty after they moved out and before my mother sold the place. Another woman might have regretted the course of husbands the apartment hosted, but not my mother. I would wander upstairs and hang out on the roof deck above our veranda. Sometimes I would climb the roof troughs and slide back down them, like sledding valley slopes in winter.

I don’t recall much about the next room – I believe it was a guest bedroom. Julie later told me that she didn’t show me upstairs because it was a mess, and that’s where the bedrooms were. This ground floor room was where my mother slept, my youngest sister in another twin bed, and me in my crib until Norine moved to the front bedroom. Then I took up the other twin, next to my mother. She must have bought the blonde wood twin set of beds, small nightstands, and blonde bureaus when I was old enough to occupy the matching twin. Most of my clothes kept to the tall bureau, so the closet was mostly hers. A large mirror was attached to the back of her low-slung bureau; does that make it a vanity? I wet the bed as a kid, but may have been over that by the time Sis moved out of the room. Would Freud call this Oedipal, my discharges in the same room as the matriarch, which she forever hated as a term applied to her. She was a single mother, widowed by one husband and abandoned by the other, who had achieved upper middle class status in Chicago but was now faced with raising a trio of daughters and a solitary little boy on a receptionist’s wages. She was doing what she had to do to make it right. There wasn’t much power in her position, but she was smart, and wanted advantages for le bon fils.

The kitchen hosted family gatherings the way tailgate parties anticipate the game. A big gray stone pattern Formica and chrome table centered the room, with leaves to make it bigger, just like the dining room table. My sister’s boyfriends must have glommed on to my mother’s sense of style, from the heavy antiques in the dining room, to the blonde wood bed set in her room, to the crystal goblets, and the big kitchen where everyone was welcome. It was wide-open, plenty of windows, with a back porch that could host a few chairs for shelter from the rain, and otherwise the new flagstone patio. A breadbox held some foodstuffs near the stove, a coffee pot percolated on the stove each morning and evening, Edwards her preferred brand, but a narrow pantry on the north wall west of the kitchen held the groceries and cereal staples that filled recipe requirements. Alas, the pantry is gone, a laundry room now, but the kitchen remains, and has a good feel about it as a family gathering spot. However, many a night I sat at the table long after dinner because I didn’t like vegetables and was told to eat them. I usually secreted them in my paper napkin when no one was present, and put them down the cleanout in the bathroom. That’s probably why Mom employed Garvin’s sewer service, which I use to this day for my own property.

I remember the bathroom was big, and Julie agreed. Three times the size of most urban baths. She said that they had moved the tub from the east wall to the south, eliminating one sink, since there were two across from each other. We took baths on Saturdays like most folks, and by the time I got water, it was cold, so hot water in pots from the stove supplemented my bathing. I remember once Jim, Norine’s beau to be, fell in the tub, too drunk, everyone hanging out in the kitchen and bathroom. With the sink and the washtub across from each other, it was as though it was originally a boarding house, but I never heard that. Just a big farmhouse on a corner — probably not a farm when the Highlands was being built, but rather a suburban plot that suggested wealth in a middle class way. A huge bumblebee one time invaded the house, occupied the kitchen like its hive, and my mother and three sisters and I huddled in the bathroom planning strategies as to how to whisk the bee away, since the only weapon in hand was the broom we grabbed from the pantry before securing ourselves in the panic bathroom. Each girl ventured out to bat or shush or clobber the bee to no avail. Finally, Marylyn pushed it out the door. I was the man of the house hopelessly coordinating the attacks. The family of women and one little guy stuck it out, to scurry the bumbler out.

She was no doubt surprised when I asked Julie to see the basement. I explained that I dreamt mostly about that space, where as a child I crawled through empty chinchilla cages made into a warren of tunnels. Julie said they hadn’t done anything to that space, and so I was grateful to her allowing me to take a quick look. The different spaces for a workbench and storage and clothes lines were still there — that’s where our wash machine had resided. The outdoor hatch and stairs were no longer accessible, but the furnace room was still dark and foreboding, as I remembered it. That basement will continue to ground my dreamscapes.

When Julie invited me to tour the manse, I told her I could take my bike cleats off, but she said no worry since she had a family always tracking through the house. That was nice, but I could hardly ask for a tour of the garden, the corner lot of grass that Norine faithfully mowed, who requested from Mom one of the first gas mowers to make her life easier. The new owners had long ago switched to making it more of a cottage garden, perennials and ornamental grasses growing alongside fruit trees and the new chicken coop. I wanted to tell Julie about the twister that came through the neighborhood from the southwest, churning sheds and fences before arriving at an old elm we had in the yard, which it tossed between our house and the new ranch next door before it exhausted itself. Front page of the Denver Post when I was a paperboy — that was fame for a day in North Denver. I wanted to tell her about the patch of soft fescue beneath the maple where I would lie down and daydream on summer days in the shade. From the upstairs porch climbing onto the roof where I slid down troughs catching hold of a dormer before I vaulted over the gutters. I could live in the treetops of big elms and that one maple which were planted when the house was built. There were so many notes to compare. I just sent an email thanking her — I hope she responds, so I can perhaps view once more the interior place before retiring to my memories and imagination.

Afterword:

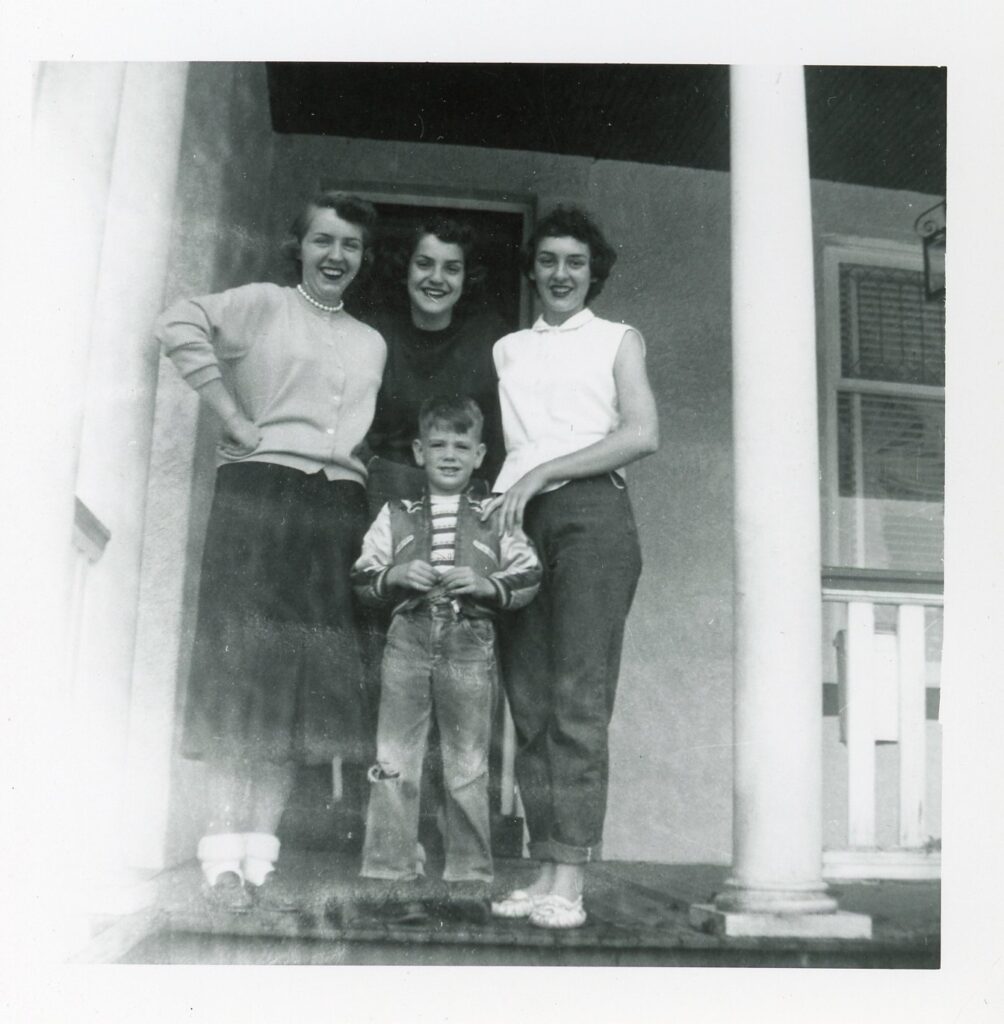

Geraldine who goes by Gerry who lives across the street still in the same house her father built and was my youngest sister’s bestie, who cruised the Scotchman with Norine, me sitting in the back seat eating a Horrible Burger or a Sloppy Malt, dependent on neighbors for snow shoveling since she was getting on in years, contacted me after Julie said I had stopped by, and we had lunch. She ordered burgers from Carl’s on 38th which she had been doing for decades, and we sat together and studied albums of photographs and talked for hours about my family and the old neighborhood. Her fondest memory saw my mother attending her college graduation from CU, with me in tow, although she didn’t see us then due to the multitudes, but my mother was so proud of a neighbor’s kid making it, she showed Gerry a photo of her walking to prove we were there; I’m sure Mom wanted me to witness.

Not long after Julie invited Gerry and Rae and I to an outdoor summer lunch in their garden party of a yard, with a few other friends, and so I was able to reconnoiter the house again, answering questions about the porch and the study, I got to see the upstairs, but what I recall is that I was a wild kid who didn’t talk, had sisters at my beck since I pointed for wants, cut down a tree of heaven that sprouted next to the porch, with the same axe I cleaved the couch before Marylyn’s wedding, that I would shimmy up to the balcony porch, raised by women who treated me like a prince, who found the house to be the foundation of character we all encounter in our earliest years, but I was born there and lived in the house until I was sixteen, which was unheard of in 1950s Denver, everyone on the move, and my mother thankfully stuck in a big old house that she was lucky to have found. You can go home again but only for a visit, a tour of memories; the basement and furnace will live forever boding in my dreams.