Monday, October 3, 2016

10 AM and I’m heading to Chicago from my home in Denver

I’ve made this trip a score of times over sixty years, since I was a youngster sitting in the middle of the front seat driving back to see relatives in Chicago with my mother and three sisters. Picture that naïve kid straight backed but barely able to see over the dash, the model of comportment, situated between his mother and youngest sister, still ten years older. North Denver is now known as the Highlands, a hip neighborhood of new steel and stucco apartments, condos, and old brick houses, where the Irish, Scot, and Italian immigrants found affordable housing at the end of the nineteenth century. John McEnroe’s National Velvet red plastic intestinal sculpture marks the new 16th Street Pedestrian Bridge, the spot where we ramped onto the Valley Highway back in the 1950s.

Living in North Denver across the valley from Skid Row on Larimer, I saw the flood of 1965 crashing the bridges over the Platte at 15th and 16th. Before the storm, we would wander down to the valley to spit on cars from the viaducts, until one hotrodder exited and tracked us down to wipe down his ride. First Chicago trip I recall, Marylyn took over the driving out of town; twenty years old, she got a ticket in Keenesburg for not observing the no-passing zone of a solid yellow line, on the two-lane US 6. She complained to the officer that she was back in her lane in time, thinking that her testimony would save her, but he knew we were from the big D because Colorado license plates denoted the county you were from with a lettered prefix. I was just a kid, and counted Marylyn as my hero, because she was beautiful and knew what she wanted, but she was as innocent to the ways of the West as much as I was a naïf of a son in a family of women.

To get to Interstate 25 and I-76, I take Speer Boulevard cross-town, since it’s one of those great parkways that exist in cities across the country, following waterways that don’t fit a grid. Paralleling Cherry Creek, this parkway was built under Mayor Speer during the City Beautiful movement of the 1920s. It was one of the first streets I became familiar with as a kid — we rode our bicycles down it on a weekend to get from North Denver to Celebrity Sports Center on South Colorado Boulevard. We didn’t know any other route, since that was what our parents drove to cross town, the Valley Highway being more circuitous. A policeman stopped us and told us that bikes weren’t allowed, but he let us continue because traffic was light and we didn’t know better. We were headed to Celebrity to bowl and swim and watch the slot cars race on a huge track. I didn’t have a slot car but the older guys Jimmy M_______ and Richard P_______ did.

I-76 parallels the railroad spur that early movers and shakers in Denver financed to attract business to Denver from the transcontinental railroad, which runs east to west near I-80 through Nebraska into Wyoming. The highest point of that original RR line was near the Colorado-Wyoming border, where HH Richardson created a granite pyramid in honor of the Ames Brothers who built the railroad. Unfortunately, the line was relocated after just a few years, to take advantage of a gentler crossing, and the Ames Monument sits outside most people’s purview. It’s worth a visit to see this stone block pyramid where the Ames Brothers face the plains. A buddy and I stopped there a few years ago on a clear windy day on our way to Medicine Bow, where we hiked the Snowy Range, and on one 11 mile trek, took in the high Rocky Mountains with acid-induced clarity.

When I was a kid, a neighbor who lived across Bryant Street moved to Fort Morgan with a new husband who went by the name of Pinky, a nebbish gentleman. Fort Morgan represented the small town charm that Denver was disavowing come 1960. Charlotte had raised a couple of boys, twins, who were about ten years older than me. I’m not sure what happened to her first husband, but Charlotte liked champagne, and wanted my mother to drink with her on Saturdays, starting early. My mother liked Charlotte but was reluctant to drink her weekend away, so she told her to bring French champagne if she was going to stop by. Charlotte did just that. Pinky got her to stop drinking and they bought and ran a motel in Fort Morgan. My mother was a receptionist for three Italian doctors, and although they were nice, she made a pittance, for there was little work to be had by single mothers. I remember her copping the look of a Registered Nurse in her white uniform, polishing her two pairs of shoes with Sani-White every day or two. She studied at home, correspondence courses, for many years, wanting to follow Charlotte into hotel management, but that never occurred. My mother studying while I did homework instilled in me the demands of education plus ambition.

My migration out of Denver through Hudson, Keenesburg, to Fort Morgan reflects the route most migrants took to arrive in Denver via the high plains of eastern Colorado. With Mom’s arrival in 1946 from Chicago, a true metropolis, she bought a big house in the city. She was determined to make her way in the West, after losing a husband to TB. Booming Denver represented her chance.

To drive the thirty miles from Denver to The Pepper Pod in Hudson for one of their hamburger steaks meant a holiday for the family, a Sunday sojourn through farm country. That was Denver’s idea of cosmopolitan dining in the 1960s, unless you went to Laffite’s, which didn’t last long once Dana Crawford revived the 1400 block of Larimer, turning Skid Row into Larimer Square. The modern Pepper Pod may have meant an interminable ride for a young boy, but the savory taste of the steaks whetted his appetite.

The high plains tend to brown out by October, but last year because of the rain through the summer everything remained green. The last time I spent much time in the Brighton area was when I started a business as a landscape designer, and put in the plantings around a medical building. Big accent rocks, ornamental grasses, perennials. Those were my specialties, now de rigueur. I meant to mimic the elements of the natural landscape, but little that we see across the plains is original. The clouds and the horizon line best define the West.

This isn’t Montana but it’s still big sky country, the high plains rising to the ranges of the Rocky Mountains. You can see in every direction without many obstructions. Imagine the plains grasses instead of the corn that is grown now — the grasses and later the wheat would have swayed in the wind like ocean waves. The corn is stiffer, less lively. The sky recalls a time when radio waves rippled across the plains, AM broadcasts that I heard as a kid coming from Oklahoma and Texas, Buddy Holly stuff. AM radio these days is talk, talk, and more talk, about religion, sports, and news, besides the Spanish music stations. The frequencies offer either propaganda or corridos. The skies are now crowded all day.

I detour off the interstate from Fort Morgan to Brush, and although the road is narrower with a closer view of the surrounding countryside, the landscape remains the same. Coming into Sterling, though, I see the line of trees that grow in the South Platte River valley. These trees line the river into Nebraska. On the ridges above the valley, to the west, wind turbines fan along the wide horizon. Historically, pioneers would have sought the tree line for water; these days, we look to oil rigs and wind turbines for our life support systems and landmarks.

Pulling into Julesburg for a spot of pasta salad packed for the trip, I lax my legs outside the Depot Museum. I remember my visit last year on Pedal the Plains with a friend whose father in law had researched the Pony Express. Riding a bike across the plains offers a closer look at the contours, vegetation, sun, rain, and wind that inhabit these flatlands, that those riders delivering the mail faced hourly and daily, for nearly two years, until the telegraph made the riders obsolete. Across the Nebraska border, I’ll catch the interstate and hightail it all the way to Chicago, a direct route that bypasses the small towns that bordered Steinbeck’s Mother Road to the south. The interstate system didn’t follow original trails as much as it was built to move the military and commerce across the nation.

When I was 10, my sister Norine who was still living at home convinced my mom that we could drive to Chicago over the weekend for Aunt Charlotte’s big wedding anniversary and reunion. We had learned that driving straight through was faster than even the streamlined silver train car called the Zephyr that ran between Denver and Chicago. Charlotte had been my mother’s best childhood friend, cousins of the same age with flapper notoriety. Norine could drive as well as my mother, and so we left on a Friday afternoon, arrived in Hammond, Indiana the next afternoon in time for the big celebration in the park – Charlotte’s husband was an Old Style distributor, so the suds were flowing, along with brats and potato salad, a German American affair. We spent the evening engulfed by the relatives, one of the few times I visited with them. We took off that night so my mother and sister could be back at work Monday morning. My mother’s age prevented her from doing much more of that kind of driving, she was in her fifties, but my sister Norine did it until she died in her sixties, just getting on the road and driving to far away places in short amounts of time.

Wonder what I absorbed about this landscape as I was growing up? It took me a stint studying in western Massachusetts to understand the difference between Eastern and Western horizons: the East was forested, with hardwoods like oaks, and sugar maples, and you could only make out a blur of woods on the horizon, or a confusion of colors in fall. Returning to Denver after graduate school, I realized that I could pick out nearly every tree on the horizon. Western forests are not as dense; the underbrush, vegetation is sparse. Aspens radiate a gold glow, a bit of orange added by willows and scrub oak. Not the autumnal fireworks of the east. The line of trees along the Platte provides a backdrop to the tawny grasses of the plains. I’m coming up to Sedgwick, which I can only imagine means the place of sedges or sage. I later learn that the town and county were named after a Union general in the Civil War. How appropriate to find a person with a name indicative of the big sage that marks the western plains. Names never impressed me as meaning much outside of wealth and fame until I started studying Victorian novels where the authors sought to expose a new social system beyond institutional religion, and names became signifiers.

Seems like the winds are always blowing across these high plains — you experience this even more in Wyoming, but going through Nebraska the wind is evident, and I expect to see more turbines. About the only trees are cottonwoods, or poplars and willows along the streams, or dry washes of blue stem that fill with water in the spring. Cemeteries are where you find a mix of shade trees, conifers often guarding the gates. Most of the elms across the Midwest contracted a leaf disease in the mid-twentieth century. Luckily, Denver saved many of its historic and stately American elms that line its parkways. By the time Dutch elm disease reached the Mile High City, arborists knew enough to prune out the dying trees immediately, and carefully monitor the remaining trees. Another Great Plains tree the Osage Orange was prized for its hard wood in making arrows. Settlers found thorny Osage hedges useful for corralling cattle.

Farmers in Nebraska have only started planting hedgerows and windbreaks over the last thirty years, although FDR promoted the Osage Orange as the Shelterbelt tree after windstorms of the Dust Bowl eroded the topsoil. They had removed all the obstructions to corporate big tractor farming during the mid-twentieth century; “get big or get out” they were told, fertilizer enabling them to increase their yields. At a rest stop further east in Nebraska, there is a sign notifying those drinking from the water fountain that it is being treated for nitrates, no doubt due to the runoff into rivers and seepage into aquifers.

The biggest challenge my mother faced driving her 1964 blue Beetle back to Chicago with me in the passenger seat was the wind blowing across the road. I didn’t notice as an adolescent how the wind kicks up enough dust to obscure the horizon; the skies and fields become a single sepia toned grey cloud. The mountains of Colorado define the horizon line and buffer some of the winds, so the seam between sky and land is visible; not so in Nebraska.

My next detour off the interstate, which passed up the small towns that only held on through close proximity to these new roads funded during Eisenhower’s administration, finds North Platte advertising chain stores and restaurants on the highway access strip, and stores boarded up in a downtown that otherwise has preserved some of its brick streets, which constituted its original civilizing infrastructure. Small town middle America finds its towns becoming intersectional hamlets visited by trains and trucks, mobile servants to the road, with little to sustain community. The highway strips catering to commercial cargo feature tires, farm equipment retailers and resellers, gas stations, diners with showers, and maybe a few schools and churches for the region, beyond the boundaries of each town. The strip malls feature a flea market set up of small box stores, as temporary as the traffic that passes these vendors. A freight train that passed me at the Depot in Julesburg hurtles through North Platte, a double-tiered container train. The trucks on the highways compete with the piggyback flatbeds powered by locomotives bypassing the smaller towns.

From North Platte to Kearney, trees line the lazy Platte, which actually looks less flat than it did back in Denver. Lots of small ponds and lakes near the highway, water in the valley. When the sky is clear, spotted by a few clouds, what water there is reflects this speckled blue that makes the scarcity of it more attractive. Kearney looks like it has a strong economy, most buildings busy with offering medical devices and services to an older population, or hardware and farm equipment. There’s the “Solid Rock” inspirational department store, a few furniture shops, and the Nebraska Museum of Art. Brick streets that passed for historic in North Platte instead solidify the town of Kearney.

On my way back to the highway, after pizza and a craft brew at a pub where old hippies and new artisans gather, I notice King’s Restaurant Buffet, the place we visited for burgers and shakes when my mom and I made our way across the plains back to Chicago. We ordered from inside tables using a microphone like those hooked up to cars at drive-ins like the Scotchman that my sister Norine would take me to when she was cruising for guys in North Denver. To order remotely impressed me as so modern. On trips, Mother often had to order a second burger for me as I was a growing boy. Once in a railroad dining car on our way to Tucson via El Paso — Southwestern passenger train routes were drying up — she ordered a second complete breakfast for me, at a time when finger bowls were still featured, so it weren’t cheap.

At a rest stop near Grand Island, I take out the stadium seat I brought along and drink a beer I bought from the brewpub before retiring to the back of the Subaru. For so many years of hitchhiking from Chicago home to Denver at breaks in the college year, seldom do I recall thumbing the return trip. My mother would give me money for a standby seat on a plane, when they were easy to come by, or I shared a car with friends from college, or someone got a drive-away, a car that people relocating wanted driven to another state. We would never stop except to get gas, or relieve ourselves. This night, relief for me is on the new Nemo air mattress and bag I retire to in my covered wagon.

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

8 AM east of Grand Island

A bit like car camping, but I’m sleeping in the back of the Outback. Plenty warm with the bag and insulated pad. Up three times to pee, normal, but the rolling over to the sound of braking semitrailers replaced my tossing in bed tuned to the train whistles back home.

Town names along the way: Gothenburg, Odessa, and Minden, where the Pioneer Village greeted visitors with its signs for hundreds of miles back in the 1960s. I don’t recall ever stopping at the Pioneer Village, but the signs marked our route through central Nebraska. The towns named for places in Sweden, Ukraine, and Germany represent the diversity of European immigrants who farmed this region. Where is the island in Grand Island? I’ll explore this on the return trip.

Slight showers in Nebraska, a sky so gray in every direction, shades of gray which allow little sunshine to penetrate the wide expanses of corn fields, for cattle fodder and corn syrup — let’s fatten everyone up. Will the corn decimate the soil like the wheat grown at the start of the twentieth century that led to the erosion that facilitated the Dust Bowl? A squall of starlings breaks over I-80 — perhaps they’re picking up their daily bug counts in light of overnight showers?

Music means all the more as I travel across these westerns plains. I have an iPod with 5280 songs, four CDs as backup: Sixto Rodriquez, Tinariwen, and Hank Williams’ Greatest Hits, a phone with another twenty CDs, from King Krule to Patti Smith to the Allah-Las. Now you can even pick up National Public Radio across much of Nebraska. How many ways can I be connected? From the Mother Road to the Information Highway, from Woody to Bruce.

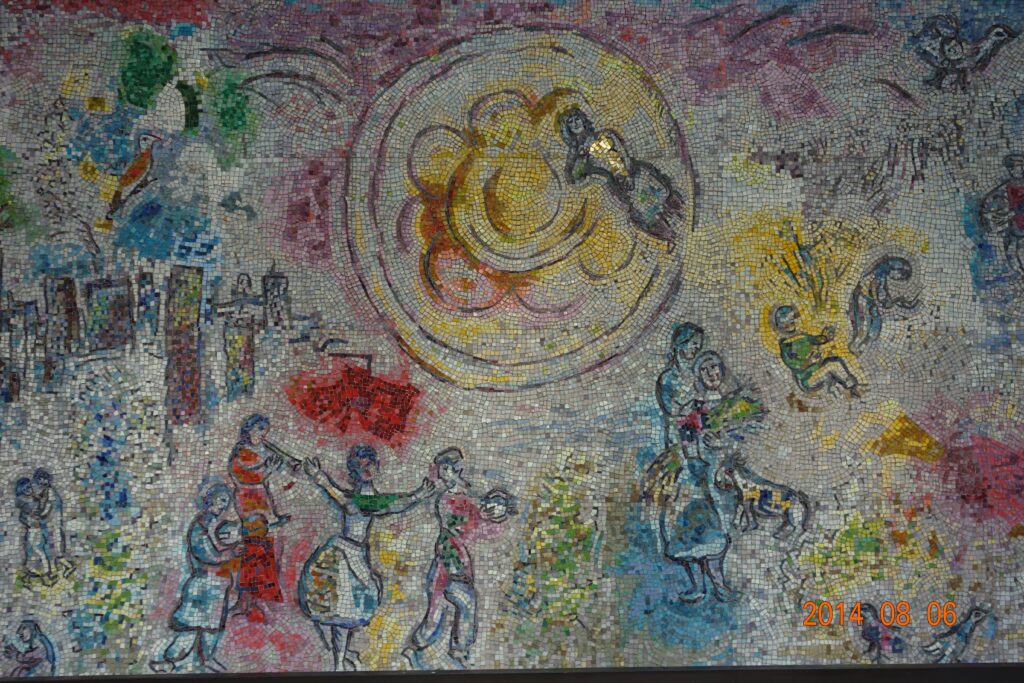

Stop in Lincoln at the Haymarket for breakfast, but most places cater to an office crowd that hasn’t arrived yet, so I try Cook’s Café on the east side, checking diners on my phone, and travel US 34 to get there, through miles of strip malls and highway fast food outlets, where people get their sugar jolts to continue their driven existence. The corn beef hash is fine, waiters extra nice comment on my Lucky Ramen Cat t-shirt and keep my coffee brimmed. I see some nice older suburban neighborhoods exiting the city to the northeast, grabbing the Cornhusker Highway, US 6, to access I-80. A few nice houses in these towns across the plains mark them as livable. Maybe an art deco bank building, library, or school that’s been preserved. Little public art like the Ball Sculpture or Oldenburg broom and dustpan that now place Denver in the tradition of Chicago, its architectural record of the late 19th and 20th centuries accented with art by Picasso, Miró, Calder, and Chagall.

I’m still 30 miles from Omaha and it looks like I just crossed the Platte — lots of brooks and hills covered in trees, riparian deciduous varieties, mostly cottonwood, which were no doubt a welcome site to anyone crossing the plains. Trees meant water, an oasis in this desert of the plains. The Holy Family Shrine in Gretna, Nebraska, just west of Omaha, welcomes the traveler as a new respite, looking like a blonde frame structure for a barn, only narrower and taller, all glass paneled, soaring above a hilltop: Nebraska’s family values version of Philip Johnson’s Glass House or Lloyd Wright’s Wayfarers Chapel in Palos Verdes.

All the times I travelled this route, I got off the highway only once or twice in Omaha — it seemed like such a tangle of highways and spread out suburbs. We happily stayed on the interstate since we had at one time been forced to drive all the business routes serving cities before the super highway was completed. The local route may have made the trip interesting for its side long glances into other communities, but it delayed our arrival. I was destination oriented, and the plains were only passable as landscape, the cities dwarfed by Chi-town. I craved the man-made artifactual scrapers over the sprawl of agribusiness.

Although Omaha sprawls for miles around its city center, the area is covered in trees in the Missouri River valley, a mix of trees and muted colors this October. Nonetheless, with the number of highways, truck stops, and transportation related businesses, it remains a hub of commerce, as it once was for river traffic, the Missouri and Mississippi course comprising the longest river in the world. Council Bluffs looks even more the part for its transportation services, Sapp Brothers, and truck depots. When my mother and I drove it we would drive up the bluffs on back roads, to make the interstate connection, before the emergence of these trucker outlets. Council Bluffs as a gathering place for outfitted wagon trains was better imagined without the cloverleaves and traffic.

One trip back with a group of students I pointed out to a girl from Littleton whom I’d made out with over the summer that the orange glow in the sky was from crime lights in Omaha. She wouldn’t believe me. I should have known better with a girl like her, naïve was I in dating, after buying her dinner in Larimer Square that summer when the waiter took all my cash thinking I was leaving an impressive tip, but especially when she ignored me at a bar on South Broadway hanging with her high school friends. I was with a buddy. Rejected, I broke a pilfered beer bottle against the factory building next to the bar, and we waded the Wash Park Grasmere Lake — we never knew it was only three feet deep; we were looking for an illegal skinny dip, and spent more time pulling our legs out of the suck and muck.

Underwood in Iowa sounds like a spot where the pasturing cattle would gather. There are more hedgerows mixed with crops, perhaps due to the topography, which diversity also makes it more attractive than the monotony of crops across the flatlands of Nebraska. I expect to see more trees all the way across Iowa, right from the bluffs, where you first encounter these rolling hills, punctuated by water courses, gullies, streams, where trees will grow, and what was probably more attractive about Iowa to me as a youngster, trees and rolling plains, the savannah that E.O. Wilson says was the landscape of human ancestry.

Adair has a huge wind energy project, turbines riding the windy ridges of the western part of Iowa. In Stuart, the town name is stenciled on the turbine shaft at the center of town. Dexter is a nearby town, but is this the shoe outlet? There was manufacturing at one time across the plains, with different towns specializing in different products.

I’m not sure I saw any wind turbines in Nebraska, despite its moniker of being the Windmill State. Everywhere in west Iowa, these icons of sustainable energy positioned on the ridges suggest the look of the Netherlands. Iowa bills itself as the center of Danish culture in America, where windmills also play a significant role. The blades of these turbines are flying down the highway on trailer trucks that have a long metal erector set link from front to rear. The shafts are transported in sections. Ask yourself if you want to ride RAGBRAI anytime soon, the summer bicycle tour across Iowa, considering the wind proponent. I’ve asked myself the same after riding Pedal the Plains in Colorado its inaugural year, beset by wind most of one day, as similar trucks carting the shafts and blades of turbines whizzed by us bicyclists trudging the country roads.

More names for the book: Colfax, named for a Vice President and nominally the longest continuous road through Denver, maybe the US; and Mingo, a tribal name, but also the name of one of the Denver Bronco’s greatest players, Gene Mingo, placekicker. More American names, Winterset and Van Meter, but this time they mark the birthplaces of John Wayne and Bob Feller — the “Heater from Van Meter” probably threw fastballs under those covered bridges of Madison County.

After my mother replaced the old Chrysler with her blue Beetle, she would battle the wind on the ridges and the blowback from trucks across Iowa. It was up to her to pass semitrailers on the down side of hills. Two lane highways and the people’s car, the Volkswagen, against the forces of nature and industry. We travelled for days: we considered the spur of I-76 in Colorado and the Illinois leg to be the bookends to the trip with the major chapters of Nebraska and Iowa comprising the two big drive days, the windy flatlands versus the rolling rises, the vertical component of troughs and ridges breaking up the monotony of the first day’s long view.

I take a detour off the interstate to see Grinnell, one of those famous Midwestern liberal arts colleges, with what appear to be many new buildings, no doubt due to the college’s generous endowment. It doesn’t have the character of Lake Forest College, with its ivy and mix of historic styles. The town does have the Louis Sullivan “jewelbox” bank building, certainly a landmark. I drive US 6 for a while. Many houses painted white, the idyllic farmstead of the Midwest, but there’s also a new Monsanto facility dressed in the same white with green trim. This is the grain goodness of the stolid home-life that big chemical brought to America. And Brownells manufacturers firearms nearby, another base indicator of American capitalism.

Slowing down, traveling the two lane US 6, a person can see the contours of the landscape up close, the hollows and ravines in the topo of the land, and the mix of crops in these smaller holdings, the need for culverts in the swales that carry the water underneath the roads. Like the New England farms rising again as small batch organic growers, once bordered by stone walls but abandoned for the bread basket of the Midwest, these Iowa plats are conducive to growing a mix of crops suitable for farm to table gastronomy.

I see one house where the man is riding a mower over an apron of green grass around his home, the fields duly plowed and planted radiating out from the house and barn at the center of the plot. The house painted white, with green trim, and the overweight woman rocking amidst her rainbow of colors annual garden. Does she win prizes at the county fair for her flower arrangements? Are farm families overweight because of farm mechanization, and corn syrup duly added to all foods? Didn’t seem like there were many fat people on the road amongst the croppers exiled by the banks during the Great Depression.

US 6 is called the Grand Army Highway. I expect there is some real connection rather than just a dedication to a president like so many of our highways today. They are like sponsored stadiums: who gets the naming rights, a beholden congressman? As it turns out, this highway was dedicated to Civil War veterans of the Union army, in the 1930s, because it connected major cities in the North. I don’t think that they marched these traces; was it another congressional handout, to honor the warriors of war in the republic?

I’m going through Homestead and then Amana, which is too cute for words — wineries, breweries, honey and jam shops, and museums dedicated to telling you how important the Amana colonies were to a movement dedicated to craft. All wood sided and gray, looking like Shaker settlements in New England. Where do Amana refrigerators come from? They started in Middle Amana, another sign of manufacturing expertise from Middle America.

Enjoy a great dinner at the Barley and Rye in Moline, after a few Blue Moons and Beams at Tommy’s. Dark as I head to the first rest stop in Illinois. Missed the John Deere factory. I recall that my wife and son stopped there with her folks on a cross-country drive — we still have his metal pedal tractor from that trip. Have leftover pasta for a treat tomorrow.

Wednesday, October 5, 2016

7:30 AM I depart the Sauk Trail Rest Stop

This was the western terminus of an animal trail that ran through Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan used by Native Americans and early Europeans. Illinois appears flat compared to the rolling hills of Iowa. Back in landscape school, I had heard that it was all woods before it was farmed, from a teacher who attended university in Champaign-Urbana. There are still copses of trees about, plenty compared to the barren flats of Nebraska. The interstate doesn’t intersect with many trails of yore.

Water flows through deep ravines under tree cover, much like the ravines I found in Conway, MA, where I attended landscape school, as well as Lake Forest, IL, the place of my alma mater. In graduate school, I attempted to make my way to school through the ravines one morn, rather than the ridge roads I typically took. I should have known better, but as a Westerner, I figured I could hop the streams that pulsed the gullies. I didn’t count on wetland furrows that ran half way up the ravines. I returned to my house to change my pants and shoes before attending classes. Many waterways, and names more redolent of the North, like Ottawa. There was a disc jockey on KIMN radio, which held Denver teens’ ears tight to their transistors and car radios in the 1950s and early 60s, we once visited the little studio on Sheridan on our bikes, who made a crazy call of “Ottawa” which impressed us as funny. Illinois residents fortunately preserved the silent “s” at the end — who wants a noisy name?

I drive into Chicago through all those southwestern suburbs that were built on white flight. A breakfast of eggs and pancakes, coffee, and orange juice at the Family Pancake House, your typical highway diner, as I sidle up I-55 to 79th Avenue, and follow that for ten miles east to see the block where my Aunt Norine lived, which I visited as a youngster. These ten miles could detail the history of migration to the Second City through its strip mall suburbs, as restaurants and stores signal different population waves.

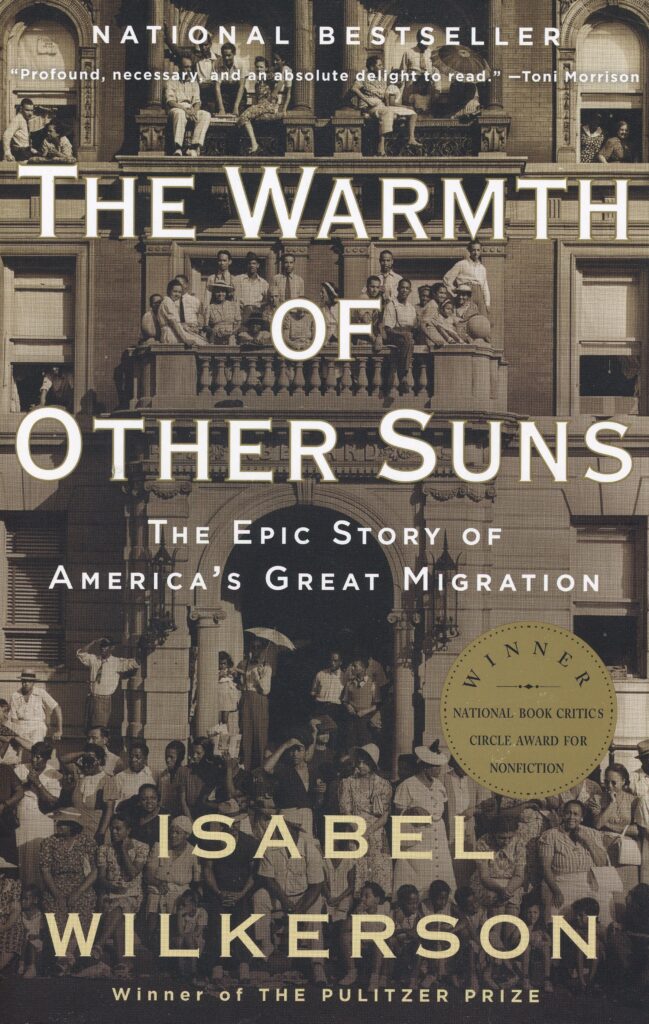

During the Great Migration of black people from the rural South to the cities of the North during the first half of the 20th century, African Americans were forced into housing on Chicago’s Southside by realtors and planners. My aunt’s house at 79th and Sangamon became part of this prejudicial plan, and she fled to Hickory Hills, and forever held a grudge against African Americans, although her city bosses were at fault. Continental Airlines once put her on a flight to Denver next to a black man, and she made a major fuss, calling Jim Crow, vowing never to fly that airline again, carving the blame on my sister Marylyn’s husband Jack who worked for Continental. Eileen and Joe, who harbored racist resentment from his youth in Pittsburgh, became the family darlings of Aunt Norine. When I was in college, I shared Thanksgiving with her at Eileen’s place near Chicago, and naïvely expected to change her mind regarding race equality. I was attending college on the North shore, at a liberal arts school that admitted and scholar shipped more Blacks than other schools across America, and my freshman counselor was a beautiful soul brother from Teaneck. Segregation and institutional hate run deep through the Second City. I never saw Aunt Norine again.

Blocks south of 79th near Sangamon exhibit nice looking brick two story homes, with large signs on nearly every corner declaring the pride of that particular block in their properties and their intolerance for any gang like behavior: no drinking on the street, no cussing, be safe. Sangamon is blocked at 79th, creating a cul-de-sac that limits through traffic, eliminating drivebys. People in this neighborhood are reclaiming their properties and lives. It appears that the folks who bought Aunt Norine’s place are as proud of it as she had been till she felt compelled to move.

It was a stately brick walkup, with two more floors than my home in Denver. I remember the back stairs and landings on the different levels, lookouts for a youngster. I played with a remote controlled sailboat on a linear lake when I was a kid. Auburn Lake Lagoon had ornate bridges and fountains. The toy boat must have been one of the first available. Aunt Norine was rich from what I knew — she paid $5 for parking downtown, and worked for the president of Union Carbide.

The South Side streets form a grid, like most of Chicago as it veers away from the original trails and diagonals that originated at Lake Michigan and moved northwest. Driving north through the hood, I notice a few abandoned buildings and loiterers, but a new Whole Foods is open at 63rd and Halsted, and the Kennedy King College looks like a vibrant institution. I drive 63rd to the lake, moving through Jackson Park to the outer drive. Frederick Law Olmsted installed this landscape for the world’s fair honoring Columbus; Daniel Burnham installed his White City near the University of Chicago. The name came from the white plaster of the neoclassical sheds that housed exhibits, and from the extensive use of electric lighting. The name should have been enough to discourage black migrants from moving to Chicago.

One of the great boulevards of the world, Lake Shore Drive in Chicago showcases parks, yacht clubs, bike paths along Lake Michigan’s strand, and a beautiful selection of high rises extends out into the lake, beyond the Prudential Building which was one of the first built. Even the CNA building on Wabash looks attractive as a red metal box — I worked there as a computer programmer for a stint right after college.

As I’m driving up the Outer Drive to arrive at Fullerton, a spot where I think I might be able to find a room, I remember that I walked with D down the middle of the Outer Drive one day after a blizzard had shut Chicago down — one of those grand snow days, sunny and bright like a Denver day, but two feet of snow obscuring the walks and streets so that new paths wander and old trails are pioneer fresh. I’m not sure whether I was living with her on Seminary, or in my studio on the poor end of Lincoln Park West, near Old Town. Streets without cars change a person’s perspective, solidifying memories, specializing the time and place.

Finding a place to stay proves more difficult than I imagine. I sit in the hot car at various loading zones around the north side looking for accommodation on my phone. My direct path via I-80 across the plains has turned into a morass of trails extending outward from Chicago’s elevated Loop, beckoning me to follow each radius. I finally settle on a nice apartment in the South Loop, a bit pricey but affordable, and close in rather than staying near O’Hare airport. The developer of this old factory building is trying to sell these as condos, renting them in the meantime. I could never be a developer, banking on people to follow my aspirational lead, since I seldom knew where my head and heart were taking me. After a shower, I head out on the El to my old stomping grounds. I’ve always walked cities to see them tip to toe, and this is me pleasurably recounting the jaunty steps of my twenties.

I was first employed in Chicago by CNA Insurance. After walking the wintry and blowy streets for months looking for work — no Zephyr wind warmed me — CNA hired me because they needed programmers who could talk to their personnel in understandable language, not techno speak. Peculiar job for a humanities major, but that’s where the liberal arts can lead. My introduction to the professional world lasted but six months. I bought some fine Pierre Cardin suits to look the part. The stylish blonde woman who worked alongside me didn’t pay me any more attention for all that. Was it because my eyes swelled shut one day in an allergic reaction to the city pollution, or did she really have a boyfriend? Loews bought the company during my training, and the one day I was sick from work, Mike Razor came through our department to cut employees. I took my severance pay and went to bartending school, happy to be out of the office, out of the corporate world. I even turned down an offer to be a programmer with the American Medical Association. I always thought that I could do it my way. The red skyscraper still stands out among the steel and glass of Chicago’s 20th century architecture.

I ended up at the The B.A.R. Association, on Webster at Magnolia, as day manager and barkeep. It’s the first stop I make, now named the Derby Bar and Grill, with a huge garden that extends back of where the old kitchen was. Beautiful front bar of cherry with a plate glass mirror that I don’t know the history of — it looks imported in any case, and must have been installed before I worked for Javad, the Persian cook who took over The B.A.R. from the lawyers who started it. They no doubt put in the cherry bar, wanting to leave their mark on the place. As it was, they built a bar at the territorial edge of the new migration of young professionals filing into the northwest sections of the city, following the original trails along Clark and Lincoln, and Clybourn’s railroad. These professionals would soon convert the brownstones of this burgeoning neighborhood into their owner occupied nighttime cubicles.

Before landing the gig at the B.A.R., I had scoured the Oak Street bars for work. They were full of yuppies wearing sharp suits, networking their afternoons away. I never fit into that scene, even though I could look the part. Walking with D in that Near North neighborhood, I once banged on a car that cut us off at the alley, saying “I’m walking here” like Rizzo Ratso. The guy jumped out and told me never to touch his car again. That’s the Type A personality a person had to have to succeed in Chi-town. It wasn’t me. I was tight-roping the edges, looking for a guttural city life. I sought to inure myself into Chicago’s past, eating at a Nighthawks style cafeteria beneath the El tracks, copping dogs at myriad Chicago stands, sitting at the bar in the Berghoff for schnitzel on a Saturday night. Oak Street wasn’t my scene, except for the occasional beach layabout. Although I lived on Lincoln Park West, my building full of studios was on the lower end near Old Town, at a time when Old Town was worn out, become a carnival arcade for tourists; New Town, up near Belmont where D lived before we got a place together, was busting wide open with eateries, clothiers, and music venues. When we got a place together, it was half way between, off Fullerton and a bit west, where everything was moving, out from the diagonals of Clark and Lincoln.

During my lone career as a bartender and manager, a waitress took care of me early mornings, as I would smoke a reefer before arriving at work, unlock the door, and let the staff set up. Mary would make sure I got a frozen unsweetened daiquiri — we called it a Hemingway, the drink he preferred in the Keys — and I would settle into the day on the garden patio before I had to tend bar, as we didn’t open until 11 and I was there at 10. I had my first cheese steak there — a great crew of exiled Iranians assisted Javad. They were anti-Shah and immigrated for their own safety. I once attended a party with this crew of long curlyhaired vibrant Middle Easterners — the music was Arabic, hypnotic, and they entertained me, but I felt completely out of my element, which I couldn’t identify on any chart during this time of adult growing pains.

As I’m wandering, I notice the literary street signs for all those students and immigrants gathered about, like Dickens and Goethe. I remember the bus driver who pronounced Goethe two ways, how Chicagoans phonetically pronounced it, and the German pronunciation, “for all you LaSalle students.” I remember a record store advertised Van Morrison’s St. Dominic’s Preview as “exquisite” enough said for me to buy it. I would wear my stylish suits, Italian and French, to the joints I favored in Lincoln Park where I lived. The business class would stick to Oak Street and the Gold Coast, but I was frequenting Old Town, New Town, Clark and Lincoln, buying clothes at Sir Real, and Bigsby and Kruthers. People would stare at me in the bars, no doubt thinking, “Doesn’t he know how to relax? Why doesn’t he wear jeans?” I grew up in Colorado wearing Levi’s; why would I wear them in Chicago when I had a chance to wear a French suit? The same people didn’t know what a bidet was after it was installed at one of the Lincoln Park bars. Boors shat in it, and it was removed when they should have been 86’d.

I take a picture of 2416 N. Seminary where I used to live, next to a gas station, which I don’t quite recall, since I didn’t own a car, but D had bought a new orange Vega, which I bumped into another car while driving it — she was probably as upset as I was by Pam burning a hole in my JanSport backpack freshman year at LFC, a small cigarette hole that in my mind ruined its integrity. The pack was something nice that I owned, that was new and trendy. I didn’t often have that advantage, nor did D. I walk through the DePaul campus, but don’t think I walked through it when I lived here after college, considering it a scholastic campus that was not my own. It must have impressed me as private property, like a corporate campus intended only for employees.

Stop in Kelly’s, an old Irish pub on Webster and Sheffield that was in place when I lived in this neighborhood. Remember catching a train here to the Loop, having bought a burrito at a stand, and smoking a doobie in the back car of the train. There’s now a Snarfs on the same street, a touch of Colorado. I also hit Shoes Pub, hoping for memories, but it’s a new joint with a kid tending bar, and an older fella waxing nostalgic in a scholarly way, who reminded me of a customer at The B.A.R. Association who maintained that trees were sentient beings, which I considered nonsense at the time, but I’m reading a book about it now, The Hidden Life of Trees. Chicago must have a bar on every corner, each with its resident blowhard or blowsoft.

I finish Wednesday night returning to my condo on Van Buren and Dearborn, changing, then going to Buddy Guy’s, which Donna and I should have visited but never did during our yearly sojourn to Chicago for the Midwest Clinic Band and Orchestra show where she sold her gig bags. Now it’s like Opryland, with old white people in the audience, a few of us at the bar. I went to the bathroom manned by a black porter who I gave a big tip to saying, “We don’t get service like this in Denver.” A goddamn phony Holden Caulfield line.

Thursday, October 6, 2016

I tour the public art pieces scattered through downtown first thing in the morning. I remember seeing the Picasso piece soon after its unveiling, visiting my aunt when every citizen had an opinion about it. People weren’t sure which zebra’s end they liked. No longer was public art about memorializing statesmen, but rather enhancing the quality of life, creating new orienting landmarks that invited critique. When I worked at CNA, I would lunch in a nearby bank plaza and watch interns under Marc Chagall’s direction paste broken tiles on concrete walls to resemble stained glass in his Four Seasons. Calder’s Red Flamingo was another favorite from that time. The city that built a new skyline in lightning time after the Great Chicago Fire followed it with a thunderous clap of modern art. A decade after my graduation from college, the Dubuffet and Miró and Nevelson were installed much to my delight; I had discovered these on occasional trips, and make sure I see them once more in person. A baseball bat by Claus Oldenburg revitalizes the west side of the Loop. I gravitate in gravitas.

Unlike most of my classmates, who were happy to grow up in Denver and spend time in the mountains, I envied the metropolitan life of Chicagoans. It was only in contrast to city life that I understood my lack of experience. Museums, mass transit, skyscrapers, city parks, the river and Lake Michigan represented for me the amenities of urban coexistence. I spent little time exploring the mountains of Colorado, outside of a few weeks spent in Grand Lake growing up. Although I was a Boy Scout, summer and winter camp were more an obligation than an adventure. Acquainting myself with the streets and neighborhoods of Denver as a paperboy made me yearn for the concrete passages of Chicago’s vanity fair. I loved walking and peddling the pavements, looking in store windows, hoping one day that Denver would grow its own Clark Street. I live near Broadway in Baker, and can say it has. Now I walk MacElroy Mac the King dog past Quality Paws pet store, Sweet Action ice cream, the art film house Mayan Theater and Gildar Gallery, Beatrice and Woodsley restaurant that features aspen trees and chainsaws for décor, and SoBo 151 for soccer games and Czech fare, besides the Skylark and Gary Lee’s Motor Club and Grub for drinks and music in classic rooms that would stand out in any city. Chicago demonstrated to me the possibilities of civilization; I craved to search out and invest Denver with similar benefits once I laid down some roots as an adult.

After a long day at the Art Institute, entranced by Peter Blume’s “The Rock” painted for the residents of Fallingwater, and of course Ivan Albright, always a Chicago treat, and John Graham’s “Cave Canem,“ I hit the Silversmith Hotel on Wabash for Happy Hour and a flatbread pizza, before trying to hit the dive bars in Logan Square: the Burlington is barely open, the bartender less than communicative, but great music of the early punk era blasts the speakers. Watch part of the Boston and Reds game at the Whirlaway, with a nice woman bartending, all Cubbies family. Customers fear the Giants in the playoffs. Then there is the Bob Inn — how can you pass up a place with a name like that? Turns out it’s a Sox hangout. Punks used to drink there according to the press pasted behind the bar. Seems like Chicago’s spirit is ranked by architecture, public art, bars, and music, and that’s a city already known for its great food spots. I catch the Fullerton El back to Printer’s Row, a street I had discovered after earning a design degree. It was one of the first neighborhoods reinvigorated in the South Loop. Now the clubs and condos extend for blocks.

Friday, October 7, 2016

Friday morning 10 AM

I head up to Lake Forest after a nice walk around the South Loop followed by breakfast. Driving Sheridan Road, which is the route closest to the lake that connected Chicago and Fort Sheridan. It’s where rich people have longed to live, near the water, on the shore. Perhaps it has something to do with human’s affinity for water, or the defensive position of being able to see who was approaching on the water. Most of Sheridan Road is now bike friendly, featuring a designated lane, unlike when I went to college and motorists considered bicyclists a nuisance. In my junior year at Lake Forest, I lived in Highwood and many a day feared for my safety as I rode to college on my bike.

Water coursing into Lake Michigan carved out these tremendous ravines along the shore. Handsome stonewalls line many bridges crossing these ravines: a town is named for them as well as a concert park, Ravinia. I went there once after college with D to see the Chicago symphony. A fine outdoor stage, although not as spectacular as Denver’s Red Rocks Amphitheater. Hitchhiking around Ravinia to get to Chicago was a bit of a nuisance, since there were few homes or traffic that would offer rides in the vicinity of the park, so unless you were picked up at one end or the other of that long corner, you might have to walk the distance.

During the Cambodia protests in college, Lake Forest students sought to shut down Fort Sheridan, and they marched to the entrance and blocked it. Base traffic was diverted to a back entrance, so there wasn’t much of a practical effect, but certainly the symbolic nature of the march spoke of students’ concerns about the Vietnam War. I marched as part of the First Aid troop, not sure I was interested in being arrested.

Highwood, where Fort Sheridan resides, is the town on the North shore between Chicago and Lake Bluff that offers practical services like mechanics, big box stores, and small Italian eateries. Lake Forest and Lake Bluff represent the wealth that resides straddling the traffic of Sheridan Road. Beyond those last rich enclaves, we see North Chicago where Great Lakes Naval Base is. It is clear between these military installations the bucolic Lake Forest is where the captains of industry lived when they wanted out of the city, protected and provincial. As you enter Lake Forest, you are greeted now by wild prairie gardens meant to recreate the landscape of the upper Midwest. Only the rich can afford preservation of this kind of open space, but the push to recreate these prairie style gardens probably owes its life to the legacy of the landscape designer Jens Jensen, who worked for the Chicago parks in the early 1900s.

I check in at LFC, see a few classmates that I hardly talk to, now or back in the day, and hear a remembrance from a professor who has spent most of her life at Lake Forest College, as student and instructor. One woman nearly my age looks cute, smartly remarks about the big Buick she drove as a student, but disappears after a day.

A tour of campus brings back memories and dialogues, like the mascot we never had, supposedly a bear or lumberjack. What we had was the girl with a bottle of whiskey at hockey games — she was the person who represented. Didn’t even have a football team most of my days. The buildings on campus represent a wide range of architectural styles, which I might have been aware of as a student, but only insofar as they offered different internal arrangements. Romanesque versus Modernist versus Tudor statements, all on North Campus, would have baffled me. Now it’s clear that the architects of the new Deerpath Hall were trying to match the Durand Institute, but in a postmodern fashion that comes off as reminiscent of Durand and Lois Hall. Seems like most of the modernism is being refurbished. Was the Johnson tulip design too outlandish? It seems to have disappeared in a construction zone? I envied the students who made use of this science library. Windows surrounded a glass cylinder of books, accessed by a ribbon of a ramp. I made do with my window above the entrance to the main library, where I sat for years, sweating in the heat of the sun and chilling when it was cold outside. People wondered who the freak with wide wavy hair and dark glasses was, who could be seen occupying the same seat any time he wasn’t in class. I found the traipse of students across the library threshold inspiring, competitive as I was, determined to learn everything I could. Only one photo of me survived my college years, a candid shot of the Senior Auction.

My high school history and German teacher, who knew that I had wanted to get out of Denver, had suggested I consider the small liberal arts colleges scattered throughout the Midwest. Writing away to nearly fifty colleges and universities on both coasts and through the middle of the country, I poured over catalogues and ended up applying to Brown, Fordham, and Williams in the East, and Lake Forest outside of Chicago, a city I had grown to appreciate after visiting it every few years since I was a kid. Only Lake Forest College replied with handwritten letters and a full ride. I couldn’t pass it up, and never regretted it, except for the period of my sophomore year when many college students considered themselves privileged for their draft deferments. The guilt made me consider alternatives like Conscientious Objector status, or a move to Canada. I took off in the middle of the second term for two weeks, hitchhiking to D.C., then driving to Boston, and fell so far behind, I was forced to focus on studies to retain my scholarship, dismissing the hand wringing over my exemption from Vietnam. If I had attended college on either coast, I might have been swayed by the mix of cultures, and the open horizons of water. As it was, I tended to explore the possibilities reached through academia. The limits of a Midwest existence forced my introspective observations of America in its landed and cultivated roots.

Watch the new Ghostbusters on an outdoor screen in Middle Campus for a few minutes, with a handful of students. When I attended LFC, movie nights in the Johnson auditorium were always packed. I watched the Marat/Sade movie during Freshman Orientation week — what a wakeup call. Where are students tonight, drinking in their dorm rooms, checking media? I head back to the Sunset on Rockland in Lake Bluff, which I had reserved back in Denver. Didn’t care to be disappointed by a bonfire scheduled for 9. Students might be persuaded to ring up alumni for gifts, especially scholarship students like myself, but they can’t otherwise be forced to join in the tired albeit traditional aspects of college life. The biggest event on campus in my day was the Ra Festival, an artistic rendering of a toga party, a new world celebration, featuring pickup floats of convertibles and trucks sporting high Egyptian newbies through the village square.

Saturday, October 8, 2016

I didn’t realize that Green Bay Road was the road to the Green Bay of Wisconsin, where the Packers play. Sheridan road connected Fort Sheridan and Chicago, like Santa Fe in Denver points south. We take names for granted, not realizing their historical import, their beginnings as traces and trails to become military routes like the interstates.

Walking around South Campus after watching the Homecoming parade, I remember hearing the Stones’ Exile on Main Street blasting from a dorm room, anticipating that it would become my favorite Stones’ album. The balconies of those South Campus modernist dorms encouraged people to share music as showboats. My frat brothers loved it when I cranked up the John Phillip Sousa on Saturday mornings; no one wanted to hear military marches. And people got pizza delivered to dorm rooms; that was a Domino’s revolution. After the celebration for Spike, who admitted me as well as thousands of other students over four decades, I drive around the community to witness once again the wealth that surrounds the college. The only other time I had occasion to drive through Lake Forest, I was working for a student run grounds maintenance company. I would tarp piles of leaves into a pickup bed and dump these in the ravines or let them fly out the back of the truck, rather than taking them to the city disposal site on the west side of town, where I was arrested once for dumping after hours, the same crime that Arlo Guthrie suffered in “Alice’s Restaurant.” I learned later from my mother that her father was so fine a colorist and house painter that families hired him to match paints to fabrics and furnishings in their Lake Forest homes. That was a trek for him from Chicago Heights, where his wife ran a grocery. I guess I had come a long way, too, baby, although I hadn’t taken up residence. I assiduously avoided notice in college, never signing up for a yearbook photo, hiding behind the acculturated student uniform of army fatigues and Indian cotton shirts, a curly head of hair and dark glasses, green shades in pink frames, always ensconced in an Eames chair studying above the entrance to the library.

A liberal arts curriculum provided me the prospect of open learning for its own sake, which tends to be a circuitous route, but getting where you want to go is seldom navigated without obstacles and determents, course corrections for sure. The physics, economics, and history chairs lobbied me to major in their departments, but I declined, opting for an interdisciplinary focus via the new College Scholar program. I wove most of my classes in American history and English plus several in theology into an American Civilization degree, serged by independent studies. Did I refuse to specialize in order to curiously pursue the connections between subjects? I had dropped Latin my senior year of high school to take a class in American diplomacy that triggered by interest in American studies. My degree at Lake Forest College predicated my graduate degree in landscape design that mixed planning, engineering, horticulture, and architecture. Later as a teacher, I taught classes in literature, writing, history, art, and aesthetics. Friends have remarked that I have redefined myself through myriad jobs, community and art related avocations, and several careers, but I see it as a nonlinear life in which I am constantly surprised and intrigued by the crossover companions of my studies; liberated by literature and historical context; and destined by design to investigate my environment, the place that surrounds me. The ravines that flow into the lake around and through my first college campus signify the web of interests I pursued through my life, never undertaking the direct course of the interstate; instead my mind moved from one subject to another on the blue highways, as each persuaded me of its importance and efficiency for holding my attention and getting somewhere in slow movements.

After a hamburg at the Lantern in town, which was still discriminating against blacks when I attended college (it was the lone place to eat for college students, which meant students of color had to flee the community to find a meal outside the Commons’ fare), I finish the night watching Seven Years Bad Luck in the chapel, with an alumni orchestra setting the tone. Fine accompaniment, funny bits, beautiful setting. Continue the cross cultural aggrandizement, LFC!

Sunday, October 9, 2016

Breakfast at the Full Moon on US 41, the Skokie Highway, bikers and truckers always welcome, before heading back to Denver. Traveling west on IL 176, maybe all the way to Rockford, further north than I’ve travelled before, although it seems that one time we drove through that city, maybe with students on a return trip to college. I had stayed at the Sunset Motel, run by Hindis, recognized by Spike as being close to the Silo Restaurant, where we occasionally escaped for a bowl of French Onion Soup at a minimal price. I only got there a few times during college, but it was a treat. During my matriculation at LFC, I scarcely ever got to the Lantern — only on reunion visits could I afford a meal out.

Still listening to Lake Forest College radio, WMXM, west of Lake Bluff, a fine alternative station, which only arrived after my graduation. I engineered shows on an early version of the station for a frat brother named Cooch, who was one of the first to play oldies which were starting to cause a stir for their original sounds of rock and roll, rhythm and blues; and a commuter student who had a show on Sundays devoted to classical music, but which he always opened and closed with John Fahey or Frank Zappa, vocalizing their influence. Most students were locked into the Stones or Led Zeppelin, or were discovering jazz, but these radio shows broadened my musical horizons, kept me venturing beyond the Rat Pack my sisters glommed onto and shared with me and the rock and roll of my high school years. I was leading snake dances with the science and math nerds to the sounds of Motown and picking up on Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway before they became popular. I wanted to hear it all.

These northwest suburbs are amazing for their lakes and water sources and scores of trees, Lake Crystal and Lake Wauconda. I never dealt with these smaller roads as I typically hitchhiked home along I-55, the Stevenson Expressway, wanting to get to the homebound freeway of I-80 as soon as I could.

The one time I’m sure that I visited the area near Rockford was when I was Landscape Manager of the Auraria Higher Education Center, and I flew with an associate at Civitas to inspect trees for the campus, to be planted along the Lawrence Pedestrian Mall. We took a puddle jumper for 30 minutes, and landed at a rural airport, before visiting a few nurseries in this northwest section of Illinois. After our inspections, which didn’t yield the results that we wanted, I ushered two associates around the north side of Chicago but failed to impress them with my knowledge of the city — I couldn’t settle on a bar or restaurant as I wanted to make the best impression, and couldn’t decide.

176 and 20 West comprise the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial Highway. Was it simply canonization of the General, or did he travel this route? In any case, it’s better than taking the Ronald Reagan interstate.

Great fishing trail along the Pecatonica River that looks like a lush green English landscape that John Constable might have painted. On the Terrapin Ridge near the Mississippi, Illinois looks more like the rolling hills of Iowa, with small farms and lots of trees. Headed south on 84 in Illinois to eventually parallel the Mississippi to the interstate. I change my mind about touring Rockford, or a northern route through St. Paul.

Near Savannah, the road is next to the water, but moves away from it further south. A train is blocking 84 so I cross the Big Muddy to take 67 on the Iowa side. Both are called the Great River Road. Clinton, Iowa seems to have abandoned the lush life of the river, and sold the space for refineries that look like Commerce Cities around the nation. America developed trade along these major waterways, and in turn, polluted them nearly to the point of their extinction. Most cities are now cleaning them up, adding bike trails and waterfront developments to attract people for shopping and eating, the great service industries of the late twentieth century.

In our great consumer society, it looks like the main act of socializing through the last 40 years has been the Sunday flea market. Farmers and small town residents drive through the countryside to barter their stuff. So much social contact now takes place inside, on computers, watching television, texting, so that visiting the local flea market has become the quaint substitute for church and scouts. Highway strip malls are set up in a similar fashion, a march of vendors barking their wares out of hollow, temporary, unattractive spaces.

Along the river again — just a row of houses, all with boats and docks, separating the road from the river. In Le Claire, the traffic comes to a crawl, because this town has a waterfront, restaurants, brew pubs, wineries, tourist jaunts. Motorcyclists and drivers navigate one side of the river in the morning, return on the other side come afternoon. I dawdle through the lunch break hordes.

I haven’t seen many police or highway patrolmen. Doesn’t seem like towns and counties can any longer afford to pay their pensions for the money in tickets they were bringing in. Now they seem to help travelers more, rather than shake them down. Also, the roads are better engineered, and the speeds are so high, there is probably less revenue from that source. The most police I’ve seen this trip were humping the beat on the South Side of Chicago.

Hitchhiking home from college, I would get a ride from someone to US 41, or down to I-55 if they were going that way, and that was the diagonal to I-80. Best ride ever was from a pilot who picked me up at 41 and I-55, and drove me all the way to Denver. Fastest trip, too. You could only hitch at the ramps, which was sometimes frustrating. One time I hitched with a school chum from Lake Forest to Washington, D.C., where he lived and intended to pick up a car. We split about halfway through the trip, because he wanted to stick to the ramps and I wanted to keep moving on the side roads. Two guys looking for a ride isn’t inviting the way that one can be sworn in for conversation. He beat me by a few hours.

When I moved out of the Seminary apartment with D, returning home to Denver because the weather bugged me so, I got a drive-away Dodge Power Wagon, threw all my stuff in the back, mostly records, clothes, books, and left Chicago in December flurries, drove cross country mostly on back roads, the 34 and 6 routes, and was admired at gas stations for that ride I was posing.

I didn’t always hitchhike between Chicago and Denver. One time I hopped a freight. It seemed the Romantic thing to do, and there were two guys at Lake Forest College who were train nuts, who told me how to do it, what to avoid, how to be safe. I hitchhiked down to Aurora where most of the trains were departing Chicago. I talked to a guy in the yards, and he said there was a train leaving for Galesburg, the switching yard for most of the nation, around midnight. I went into Aurora, got a bite to eat, and went to the movies, watched Change of Habit with Mary Tyler Moore and Elvis Presley — he plays a doctor and she’s a nun, which seems absurdly romantic given my reason for seeing it. Hopped a train back in the yard to Galesburg, and with the help of a yard worker, found the Cannonball Express, heading to Denver. He showed me how far back I should get a boxcar, in order to stay attached to the train and not be dropped somewhere across the plains. I packed some cardboard in there and made a cozy bed — both doors had to be left open in case one was shut, to prevent being locked in. It was a long trip, with cars constantly shuffled to sidings. Unfortunately, my car was dropped in Omaha, and I ran to catch the caboose as the Cannonball left the yard. The brakemen let me ride to Grand Island, but told me I had to get back in a boxcar when they changed crews. It was warm while it lasted, next to the stove in the caboose, but it was bitter cold the rest of the night into Denver.

Hopping the new Cannonball, I-80, I leave the lush life of Illinois behind. Iowa looks brown, the dried corn about to snap off. More great names: Moscow, Brooklyn, and What Cheer. Across the state, I find a great restaurant on the west side of Omaha, the Nite Owl, and enjoy crab appetizers, an old fashioned, jalapeno sliders, and red ale to wash it down. I eventually crash for the night at a rest stop west of Lincoln.

Monday, October 10, 2016

Gray skies as I wake at 7:45

A regular Nebraska day, flat countryside, a few trees border streams and protect houses. The corn is being mowed down to feed to cattle or turn into corn syrup; keep the fat content high.

Breakfast in Grand Island at another local diner like the one I ate at outside Chicago. I’m near where I slept the first night on my trip east, so I expect I’ll be home today. Put in lots of miles on Sunday.

I drive around Grand Island but it’s disappointing — an older central core surrounded by highway strips of trucker stops and tire stores. 30 West to Kearney looks like one long commercial strip for the transportation trade, full of fast food joints and gas stations, so I hurtle back to I-80.

It took me a long time to understand sun angles and exposure times for plant design. I can be a slow study because of my naïveté. On the high plains of Nebraska, the original immigrants who succeeded at farming must have understood that they should plant trees near their houses for windbreaks and shade. Hedgerows to stop blowing snow. Yet many of their descendants cut these obstructions out, these border plants that also attracted pollinators. Seems we’re back to instituting model practices in agriculture, usually through county extension agents.

Rest areas along the interstate are modern Hoovervilles, straight out of The Grapes of Wrath, where the homeless truck driver can sleep, where people with RVs can hover between campgrounds and services, people slumbering in the back of their Subaru wagons who just want to get down the road without paying for a motel.

People have made a permanent change, and it’s typically a luxury move, buying into America’s wanderlust by selling their homes and hitting the road in their RVs, which are supposed to be recreational vehicles but it seems they have saddled themselves with more stuff than necessary for travel. There’s a sign at the rest stop where I stay west of Lincoln that says no more than 10 hours of resting — I suppose that’s when it becomes camping. There’s no smoking at the rest stops in Iowa, where there are also signs that tell people not to pick up hitchhikers, and not just the escapees from correctional facilities, any hitchhiker. New rules for a retired community on the road. Have the National Parks nurtured this vagabond life style?

I think that these migratory patterns of Americans started during the Depression with the move to California of so many people. Looking for work and planting new roots, people necessarily traveled with everything on their backs. It was the first migration on wheels, as Route 66 became the Mother Road. The Great Migration of blacks from the South was usually accomplished on foot, hitchhiking, or busses.

The wind blows again across the Nebraska plains, but I see no wind turbines, although it’s called the Windmill State. A murmuration of starlings appear overhead, but it hasn’t rained in this instance. Perhaps they’re gathering bugs after the corn has been cut. The cottonwood and willow and elm and bluestem along the riverbanks must attract birds. The Platte runs from Grand Island to Kearney, and the strands of trees mark its location. Research suggests that French trappers called the land formed between channels of the Platte River “La Grand Isle,” but the station for the railroad was later established inland from this island.

Beyond North Platte the plains start rising — that must be the title of one of John McPhee’s books on geology. Colorado’s eastern plains come into view. The time home seems shorter, although I am driving more hours each day. Perhaps the anticipation of a vacation lengthened the trip out to Chicago?

The rest stops in Nebraska offer weather and road information, which suggest that the roads are often closed due to weather. As I gain on Ogallala, the clouds lift and blue sky welcomes me to Colorful Colorado. But the stench of a feedlot permeates the air. The odor makes me think twice about eating beef.

The Stuckeys are gone: they one time signaled stops along this entire route, but the convenience stores at gas stations and truck stops have replaced them. My fully charged antique iPod gets me from west of Lincoln to 100 miles from Denver; just a bit of NPR thrown in around the cities of Nebraska. NET is hosting their pledge drive so I avoid it most of the time, although hours of baroque music are available midday. The white lines of the highway visually signal my zoetropic advance, since the landscape persists as a singular vision. Perhaps a Nebraska native could communicate the smells and sounds that must animate this Midwestern land. I take the rail route of the Zephyr southwest to Denver.

Near Greeley, I see the mountains in the distance, shrouded in a bit of haze. The sky crystallizes. The mountains provide a stunning backdrop to the pinnacles of the new Denver skyline. John Ford said look at the horizon line, the cinematic threshold to our dreams. Chicago may have the Gold Coast, but Denver has this mountainous rollercoaster that provides a skein, a backdrop to a stage, rather than just the foreground of a lake shimmering. The Queen City of the Plains welcomes me, a stunning landscape and glimmering artifice. It has its architecture and public art, from the Johnson Cash Register building and Liebeskind’s Museum Nexus to the red-eyed Mustang at DIA and the Big Blue Bear at the Convention Center. It has its bars like the Skylark and Gary Lee’s on Broadway along with the new joints in RiNo. And there’s long been stellar music coming out of the Queen City, from bands like 16 Horsepower and Devotchka. Upon my arrival in my native habitat, it’s grace to witness Denver’s resemblance to the Chicago metro center that I pilgrimed to for so many years. And of course there’s that Western sky, as cinematic a vision as one could care to cradle.