A Boatload of Books for 2020:

I may not mention all of them, but will pay my respects to the tomes read this year, in no order, so plow your way through the entire list — some were borrowed from friends, others leant out, while Denver Public Library offered its curbside service in our joint time of need. I have delayed this survey until now, after the first of 2021, in the hopes that you have already perused all the year end lists that avalanche their way over our snowy thoughts of December, and you are now ready to hop on the Elk Bellows gondola.

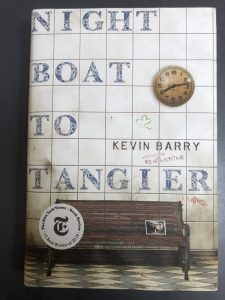

Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry has remained in my mind long after the crisp reading of the author’s wonderful language and realistic telling of a Godot type relationship and predicament. Two blokes waiting on the daughter of one of them in Algeciras, reminiscing as a means of spending their patience, recounting their miserable lives. It’s a dark version of everything Mrs. Dalloway recalls as she prepares for her party, and the language is nearly as exquisite.

There’s a different kind of relationship explored in Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends. Two women, one a writer, conjoined as friends and sometimes lovers, two different people, who become involved with an affluent couple who make them feel important, or wanted. These Conversations are just that, non-judging, wry observations, never delusional, that depict modern relationships among smart people. I’ve stayed away from the streaming series Normal People based on another Rooney novel, because the writing is too good to dilute.

Colson Whitehead followed The Underground Railroad with The Nickel Boys, which does not include the magical elements of his previous novel, instead relying on the real tragedy of a reform school that tortured black boys. The writing is adventurous and smart for a book that comes off as one more example of racial justice deferred. Whitehead makes the school the genuine, practical embodiment of the school that Ellison poetically depicted at the start of Invisible Man.

If you like historical fiction, The Lydiard Chronicles 1603-1664 by Elizabeth St.John will catapult you into the middle of the English Civil War. In The Lady of the Tower, By Love Divided, and Written in Their Stars, St.John focuses on her ancestral family whose members work, fight, and succeed on different sides, illustrating the royal conflicts that affect people at all levels of society. Think of it as Hilary Mantel light.

The book that brought me closest to crying was the elegiac tragedy of Jude who dies a few deaths, caught in the tendrils of modern professional life after a youth of abuse, who grows alongside a trio of close friends, a group that cares for each other: A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara is one of the most heart stopping books I’ve encountered, and it plays admirably alongside Hardy’s Jude the Obscure.

I thought that Tommy Orange’s There There was a great debut from a few years ago, but Leslie Marmon Silko’s Almanac of the Dead from 1991 expands on all his cultural divinities, with so many intersecting stories that the epic comes off as a Dickensian tell all from the American Southwest. It’s big and long but worth the reading to gather a sense of what goes on among the tribes that doesn’t get told in the media — fiction that casts a light on non-reporting.

Marilynne Robinson continued her Gilead saga with Jack. Since I have found her writing in novels and essays to be without comparison, I quickly picked this one up, and discovered a different book than what I expected. Jack and Della are in love, but come from different cultures, which like Romeo and Juliet, make their union more an obstacle than a treasure. Most of the book is dialogue between the lovers, and it brilliantly shows the connection between these two. The reader might otherwise dismiss the complexity of personality that Robinson depicts, and that is her gift. In Jack, she shares the intimacy of a passionate and provocative love story which the partners want despite their and other’s objections.

Peter Guralnick’s classic book on the rise of Elvis Presley Last Train to Memphis kept me glued to this account of the early days of rock and roll, and cleared up long-lived rumors of the King that I had heard through the years. A grandly detailed biography of a time and a place, of a person and a movement. Read it alongside that new Henry Adams biography for a long draft of history in the making.

David Mitchell has long been one of my favorite authors, but his Utopia Avenue shook up his fervent fans. It must have seemed superficial to some, but the book clearly elevates the story of a rock and roll band hitting the big time with Mitchell’s perfect prose. I found it as fun to read as watching High Fidelity again.

A writer and friend loaned me Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other, and I found it to be as exciting a story as Lessing’s Golden Notebook, but more humorous, entertaining. The characters are so fun to follow in their growing together, seeking identities that work for them individually, and the style keeps the wheels going up and down.

Two small books, one by a colleague and one by a former student, show the possibilities of prose in various forms. Moss Kaplan writes a letter to his young son in Boy of Mine, to be read when his son is approximately the age of the father. The first book by Marilynne Robinson about the people of a small Iowa town called Gilead featured a long letter by a minister to his prodigal son Jack, so the form has seen a revival, and Kaplan succinctly shows how wonderful fatherhood can be as he looks to his son’s future. Sammie Downing capsulates a family into a myth that says so much about fears and hopes that we all hold for our relatives, and how home and place get intertwined in our minds as we bounce from exploration to the safety valve of love. I found The Family That Carried Their House On Their Backs to be as enticing as Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant.

Walter Kempowski’s All for Nothing details the plight of the East Prussians in the face of a Russian invasion after the fall of Germany in World War II. It casts a dark shadow over civilian refugees, who hang on to whatever is left after their rise to power and eventual doom. The mood is one of earnest failure, of people casting about for a life preserver on a dark sea.

The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson from 2012 was one of my favorite reads of last year as it follows an orphan who mysteriously rises to power in North Korea, unveiling in its telling so many of the weird social constructions of that country. Its style contrasts people who appear to be related but who are intimately the same, which is only possible through the concatenations of the leader and politburo. Highly recommended.

There are other books that I read that deserve mention, but they are aptly covered by year end lists and reviews, including The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante, Rising by Elizabeth Rush, Lab Girl by Hope Jahren, All the Birds in the Sky by Charlie Jane Anders, What You Have Heard Is True by Carolyn Forché, and Barracoon by Zora Neale Hurston. There was lots of time for reading this last year, and even time for some writing.

Books I Read in 2019:

Since a friend was reading The Overstory by Richard Powers on my recommendation, I took it up again. It was my favorite read of 2018, and felt as compelling upon a second turn, for its characters, fabled realism, and narrative focus on environmentalism. I believe it to be a classic for the ages, and everyone deserves to read it.

Transit by Rachel Cusk, the second in her Outline Trilogy, sucks the reader in again through the shifting dialogues of the protagonist with strangers. If Hemingway advanced novelistic plots through dialogue, Cusk establishes the entire plot, which is hardly more than verisimilitude, in her conversations. This is auto fiction that entices a reader along lines easily understood.

I finished M Train by Patti Smith, and moved on to Devotion after seeing her perform in Santa Fe. Although Devotion focuses more on the craft of writing, in its exploration of how she came to write the introductory fable, much of her process and inspirations are mentioned in M Train. Here’s the poet punk rocker who won a National Book Award with Just Kids explaining in prose how she deserved it. No hubris, just beautiful plain talk about writing.

In her debut novel Asymmetry, Lisa Halliday reminded me of Rachel Cusk, as the situations in which the characters find themselves occur randomly, and yet everything relates. This type of writing appears to have developed in the wake of the advancement of chaos theory, where we find connections in disparate circumstances. At one time, people might have believed that god was behind it all, as everything happens for a reason, but we find ourselves discovering the social, biological, or environmental rationale underscoring life. Crows chat about murder, trees talk among themselves, we consider the path not taken. These authors write episodes that might have been called short stories but for the overlap between some characters and some events. Entertaining stories to say the least.

With the release of a new biography of Susan Sontag, I returned to one of my favorite thinkers and fiction writers. I reread The Volcano Lover by her, and was entranced once again with her post modern take on documenting the life of Sir William Hamilton, a British consul stationed in Naples who supplements his income through collecting. The book is about history, fame, geography, art, and the attraction collectors experience for the objects they desire. The story is told from a contemporary perspective inserted into the historic lives of Hamilton, Emma his wife, and Lord Nelson, the British naval hero. It’s not simply historic fiction, not aesthetics, but all Sontag:

He – for it is usually a he – comes across something unappreciated, neglected, forgotten. Too much to call this a discovery; call it a recognition…. He starts to collect it, or to write about it, or both…. Others start to collect it. It becomes more expensive. Et cetera.

Corregio’s art. And Venus’s groin. You can really possess – even if only for a little while…. There are so many objects. No single one is that important. There is no such thing as a monogamous collector. Sight is a promiscuous sense. The avid gaze always wants more.

There remain many books called classics which I have not read; some I have started a time or two, and still have not finished. Don Quixote by Cervantes was one of those until this summer. I had read Part 1 in the past, and recognized the great imagination and scope of the book, but had not finished it. I read the entire tome this year and enjoyed it no end, finding it to be the perfect respite and relief in these troubled times. I think I was goaded into taking it up again by the remark on the back cover that William Faulkner reread it once a year. That was enough coming from one of the great storytellers. It is a masterpiece of social commentary, stylistic invention, and caricatures of camaraderie that has inspired countless other classics – Northanger Abbey comes to mind for its satire of romances, as well as Waiting for Godot for its maddening friendship. Cervantes wrote at the same time as Shakespeare, and the bard’s My Mistress’ Eyes are Nothing Like the Sun has nothing on “ Her hair was more like a horse’s mane, but he saw it as strands of gleaming Arabian gold, the splendor of which made the very sun grow dim. And her mouth, which reeked of stale piccalilli, seemed to him to exhale the gentlest of aromas.” Read it if you haven’t.

After reading The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy years ago, I was looking forward to a new book by this author, and had read reviews of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness which came out in 2018. Visiting Tattered Cover on Colfax, where I browse books a few times a year, I mistakenly picked up the bargain All the Lives We Never Lived by Anuradha Roy, a Man Booker-longlisted author. Not the book I was looking for, but a wonderful read, about a woman seeking the freedom to pursue her art in the 1930s when the Nazis are coming to power and the British hold on India is tenuous. Much of the book revolves around the confusion the artist’s son feels with her departure in the company of free spirits. Like other books I’ve read about India, like Mistry’s A Fine Balance and Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, this one captures a culture that feels so different from my own.

Since I read Don Quixote, I was fortunately obliged to pick up Salman Rushdie’s take on the classic, Quichotte. Although I had read mixed reviews suggesting this book was Rushdie “light,” I found it enormously entertaining, especially in the wake of reading its inspiration. The author transcribes events and stylistic manners to a trek through contemporary America, where fact and fiction get mixed up, like our politics, and the classic Quixote. It’s brazen and great fun to read.

I first encountered Robert Macfarlane in researching the catacombs of Paris, travelled there this summer. His book Underland reminds me of Being a Beast by Charles Foster who tried to live like a selection of animals, inhabiting their burrows and trying their foodstuffs. This one explores the hidden world around us by taking us underground, under ice, through caves along starless rivers, to killing fields, and uranium vaults. It begins with caving, but finishes beneath glaciers. Always Macfarlane parallels the psychological repercussions of this subterranean exploration to the natural paths where we hide so many secrets.

Because I read the wordsmith Macfarlane, but wasn’t ready to pick up Landscape and Memory by Simon Schama, I reread Underworld by Don DeLillo, one of the last epic novels. It begins with the Shot Heard Round the World by Bobby Thomsen in the 1951 playoff game between the Dodgers and Giants, a historic hit that echoed the Cold War and the changes in the national scene during the last half of the 20th century. This novel covers earth art and Lenny Bruce and waste dumps and J. Edgar Hoover. It’s a big page turner worth a second read.

Jill Lepore always impresses me with her writing for the New Yorker, so a quick analysis of nationalism in her This America answered a few troubling questions about the use of the word by despotic leaders coming into their own around the world. She makes a brilliant case for “a new Americanism” that is liberal and proud, dispelling the nationalism held high by the likes of Trump.

I finally finished A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James, started years ago, and find that I liked the idea of shifting perspectives revolving around the assassination attempt on Bob Marley, and its expose of Jamaican culture and politics, but the drug jargon and gang warfare finally stifled my interest, and that’s why I had a hard time finishing it. Bolano’s 2666 affected me in a similar way, as I trudged through the killings of far too many Mexican women by the cartels. Both are brilliant books but tough reads.

Besides the pairing of Don Quixote and Quichotte, the book that remains highest on my canon of reads for the year 2019 is The Topeka School by Ben Lerner. I wasn’t sure where it was going when I began it, but the characters assume their identities in deep ways, and chapters told from different viewpoints landed me, to the point where I cared about each person, as complex and contradictory as Lerner makes them out to be. The style is vocab rich, through debate competitions and psychiatric analyses. This one is stronger than the lot of books I read this year.

A poet and writer friend asked me what I thought about The Winter of Our Discontent by John Steinbeck. She knew I had attended the Steinbeck Institute, but this late novel had not been part of the curriculum. I finished the year reading it, as much for its title lifted from the opening lines of Richard III that sound so appropriate in these times, as to complete my examination of Steinbeck. I didn’t care so much for the dialogue to start, but it grew on me as the main character is revealed to be a caring kind of cad, who is trying to raise a family on his honest wages as a store clerk, before he decides to take up a plan that is sure to make him a rich man. Nothing quite works as he has planned, and the complex emotions that Steinbeck delineates in a middle class breadwinner who is watching his wealthy neighbors cheat the system bear our empathy although we come to dislike this Main Street citizen in many ways. It may not be The Grapes of Wrath, Cannery Row, or East of Eden, but a strong late showing from one of our best writers.

Books I read in 2018 (some still bedside):

I finished last year’s list with a note that Barry Jenkins, the director of Moonlight, was scheduled to do a series for The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead. That is in production, but a movie he just released is If Beale Street Could Talk based on James Baldwin’s novel from 1974. Since the title is not referred to in the book, it carries a clue as to the theme of the novel – a blues life incarnate. Baldwin mentions the time in the apartments of African Americans when the darkness approaches, the twilight time when the family looks at itself and tries to be hopeful for the next generation, knowing as they do the troubles they’ve seen, praying like Sam Cooke for a “change is gonna come.” The author mentions this evening tide as he had in his earlier “Sonny’s Blues,” when nasty noises from the street start to overwhelm the family. The novel has many of the themes that Baldwin explored, from racism to a life in the arts to family and what it meant to grow up Negro, from hard jobs and prison life to the black church. This book is tougher than some of his early novels, yet tender in its talk of the young couple’s relationship. I expect the movie to be misconstrued by people without knowledge of the book.

My favorite lines from As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner are spoken by Anse about a life on the road versus in a home: one is long and arduous and shouldn’t the traveler be a snake crawling on his belly along the road; or should he gain altitude and live upright like a man in a house. Roads are for travelling and homes for standing. I think that may be why I didn’t care much for my rereading of this book that is usually handed to students as an introduction to Faulkner – too much travelling without the traditions of generations inhabiting a manse, invoking the mystery of underground roots. This book is mostly referenced as an example of shifting viewpoints. Faulkner expertly achieved this in other novels, especially from the four perspectives of The Sound and the Fury, which I may take up next in my reengagement with the author.

I traveled by train to San Francisco, before renting a car and exploring the area around Monterey. In visiting the Henry Miller Memorial Library in Big Sur, I bought the book of the same name by Jack Kerouac. A friend tells me it was probably the last book he wrote in real time, in ten days a few months after his visit to California, where he complains about being worn down by his notoriety. Like a beat visiting his self-made Altamont, Jack glosses over his drunks in the Bay Area, focusing instead on his attempts at recovery in Big Sur, and his ignoble adventures there hallucinating through the days and nights, so self-effacing, even regarding his friendship with Cassady, who is full of a vast and senseless strength. The book impressed me as nearly senseless, compared to earlier novels that at least attended the spirit of the land and the road and the wonder they held.

A bargain book from Tattered Cover was On Trails by Robert Moor, which didn’t satisfy my yearning to hear more about the origin of traces, trails, paths, and highways, but explored the idea through a miscellany of topics, including the pheromone trails of insects, which I found most inviting, and sheep herding. The focus on hikers of the Appalachian Trail, even as they seek deliverance across the ocean, reveals the target audience, which is not me.

A quick read purchased in New York was What We See When We Read by Peter Mendelsund. His thoughts clarified what I ostensibly knew about the written word. Grab it if you want to know more about how authors do what they do. It’s like a graphic designer diagramming sentences.

If a friend had not passed on Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders, I may not have read it this year. She didn’t care much for the style or seemliness of the narrative – that’s my word, not hers. I found it intriguing for the debt it owes to Edgar Lee Master’s Spoon River Anthology. A menagerie of interred souls try to counsel Lincoln and his son on young Willie’s staging in a crypt. It is so peculiar, and more so for the furtive conversations among the dead, like the poems from those buried on The Hill in Master’s elegiac work. Some conversations are historically based, other ghostly concerns are imagined. Quite a feat, and worth rereading. I don’t know that the general public will think it a classic in the long term. I’m supposed to pass it on, but I’m not sure that I can quite yet.

Another stylistic phenom is Rachel Cusk for her Outline trilogy. I’ve only just read the initial volume, Outline, but am as impressed as the critics, for the variety of storylines revealed through the dialogue and protagonist’s impressions of acquaintances. Innovation like this in writing thrills me. I needed a page-turner for a trip and bought the paperback of Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach. A fine story, perhaps a little too unbelievable, but the facts and mystery of this noir satisfy.

After reading The Hidden Life of Trees last year, I craved the fictional tomes that explore environmental consciousness with an emphasis on those plants that mark the landscape like no other. Annie Proulx manages to splice together a history of the lumber industry over centuries through her Barkskins, which should become an epic novel of 19th century proportions. The author manages to combine the humanity of many of her novels with the historical register of Accordion Crimes to record the regretful saga of tree genocide. It makes a reader understand what happened to Easter Island, only on a national, North American scale.

The other novel that pledges new awareness of the importance of forests and individual trees is The Overstory by Richard Powers. Think The Monkey Wrench Gang and Midnight’s Children, starring trees as sentient beings, and a cast of characters straight out of your most recent Netflix binge. Although I loved Barkskins for its research and history, I think that this will be the book that captures imaginations into the future. The great book for 2018. Listen to the trees for they herald, indeed secure, our existence on earth.

There There by Tommy Orange reminds me of White Teeth by Zadie Smith – he captures a conglomerate of Native American stories in anticipation of a pow wow, in the midst of a battle scene that regrettably every American has come to expect. It is topical, it is Oakland, it is the modern tribe unfolding for the indigenous. What a fine debut and heart-paced book, told episodically like many contemporary novels, with vignettes of kids and adults all too true for everyone.

It’s beautifully printed with fine paper and color plates, illustrations galore, Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson covers the real genius’s life in short chapters through a big book that reveal his development as a painter, inventor, citizen, and human in digestible chunks. Check it out before the show about da Vinci opens in Denver, March of 2019. Then you won’t have to read the signs or listen to the audio; you can just marvel.

Gerald Murnane got a lot of press for being the great unknown writer this year, a writer for writers, so I picked up a collection of stories called Stream System, and I am impressed although I think most people would balk at the Gertrude Stein repetitions trying to get to the core. His writing reminds me of the cinematographic words of Alain Robbe-Grillet, but focused on the bush roads and scrub brush of Australia, where a GPS might graphically get a person their bearings. Murnane entertains history, a sullen life, memory, and the landscape in words that read like Rand-McNally maps. I’m most of the way through the collection but intend to keep the last few stories in the hold.

So many books are on the bedside stand, still to be finished, including The Idiot by Dostoevsky, Ulysses by James Joyce, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by Agee and Evans, and A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James, which is the one I’m most intent on getting through. A few others still entice me, but Heller’s posthumous Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man, a title I could not pass up, reeks of gimmickry that is transparent and I’m sure he knew it – he may have been having fun, but I wasn’t while I read it. I will pass that one on.

Books I read in 2017 (not quite comprehensive):

On a trip to the Midwest Conference on British Studies in St. Louis, I read Swing Time by Zadie Smith, an author I’ve admired since 2008 when I took a class in Contemporary British Fiction at Oxford and read White Teeth. Although I told Rex Brown, who first invited me to be a teacher and who was with me at the conference, that I wasn’t as impressed with the book as I had been with Teeth, I nevertheless found it just as insightful regarding contemporary culture, from the status and lives and do-good enthusiasm of pop stars to the experiences of kids from crazy homes who want to become those stars. Then there’s the outsider who quietly does her job and observes her talented friend whom she grew up with dissolve into a pattern of poverty and transferred hopes for her progeny. The ending is especially stellar, and the dialogue masterful.

In June, The New York Review of Books featured an article on Wilkie Collins, so I took him up once more, after recycling my scarcely broken copy of Moonstone in my last effort to thin my bookshelves. This time I read The Woman in White and got through it – indeed, it is a mystery novel – but compared stylistically to Dickens, I don’t care for him. To me it’s a big vacation read, not the sort of novel I pay much attention to or remember.

I saw Lenne Klingaman play Hamlet at the Shakespeare Festival in Boulder as a member of an English Speaking Union group who enjoyed a picnic before the performance. In advance of the play, I picked up Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, narrated by a baby Hamlet in the womb. McEwan constantly demonstrates his ability to tell stories in new ways that expand a reader’s perspective on tried and true narratives. I was introduced to him in that same Oxford class on British Fiction, where I read Time’s Arrow. He remains one of the finest writers in English, no matter the tome.

Most of the books I read come from my perusal of reviews in the New York Review, or Harper’s, or Atlantic, or the New Yorker, or from the stores of Tattered Cover, which I visit every few months. Some are new, others are rereads, a few are bargain books I missed through the years. The reviews for Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant were tantalizing but not compelling. I found the book to be a beautiful read about older people and younger warriors, all mistaken but determined to live and pursue their loves and challenges. It suggests that all of us should be skeptical but hopeful about what our lives deliver. Ishiguro tells this tale as though it was a myth, and so our lives resemble one.

People flocked to read Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, and most were disappointed by the characterization of Atticus Finch as a man living in the changing South where his ethics displayed in To Kill a Mockingbird come under closer scrutiny, to the dismay of Scout, Jean Louise, now in her twenties, who has returned from NYC to visit her father. It’s no wonder it wasn’t published when it was presumably written, before Mockingbird, since it paints the prejudicial South at the start of the civil rights era, stubbornly reacting to the people who want a change. It’s a better book for its capture of the culture, as it portrays the ensuing battles from various perspectives, which Faulkner managed in Intruder in the Dust.

I did retrieve my favorite William Faulkner from the shelf and read Absalom, Absalom! again. It never fails to amaze me, for its audacity as a mystery told in streams of consciousness about a society so complex for its history and social attitudes that the story necessarily bears repeating through the novel, and rereading over and over. The same questions arise today, queries about race and misogyny.

Near the end of the year, I picked up Jazz by Toni Morrison at the BookBar on Tennyson. She rivals Faulkner for depicting all strata of society in a style that reveals only as much as is needed to keep the reader plastered to the page. This book dictates an immediate reread, since like Faulkner, many of the details get lost as the reader strives to follow the shifting points of view and timelines. Great language.

I started off the year with An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine, about a Lebanese woman who translates the classics into her own language for the sake of her culture. This a gift from Pat Dubrava, the poet and essayist who translates novels and teaches a class in translation at DU. It’s a great cultural expose of a country’s civil war and the lives of those who carry on, besides noting the books that the protagonist treasures, which becomes a new list of want-to-reads for the reader.

Having always enjoyed Michael Cunningham’s take on Mrs. Dalloway, The Hours, I picked up a copy of his book of tales told with new insights, A Wild Swan. I can hardly wait to read these versions to my granddaughter once she’s memorized the fairy tales we know from the Brothers Grimm. We all need to read myths from another, other sides.

I don’t read much non-fiction save for magazines and journals, but a few gifts and purchases really impressed me this year. H Is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald was a bestseller a few years ago. It’s a fascinating tale of the author’s relationship with a bird and the history of training goshawks. It’s an experiential memoir that portrays one person’s endeavor to recover from the loss of her father. I stick to books that feature splendid writing, and this one does that in talons. I read a review of The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben, a former German forester, and although I heard a fellow suggest that trees could be sentient some forty years ago in Chicago – an idea I pooh-poohed at the time – I felt it was time to give the idea a chance, and Wohlleben is good to the task. As the jacket suggests, “…a walk in the woods will never be the same again.” This book makes the reader conscious of our environment and our place among the trees at the interactive root level. I still can’t get over Being a Beast by Charles Foster. He does for living like animals what Thoreau attempted to do for living a simple life of farming, observing nature. Sometimes it’s hard to stomach, but entrancing.

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen illustrates an immigrant generational view of America, this time by a Vietnamese writer about a refugee who lands in America after the Fall of Saigon. He joins that group of writers who have written so assiduously about the American condition from the perspective of the immigrant, like Alvarez, Tan, Danticat, Hijuelos, and Diaz – the new American voices. This is a great thriller that interweaves the war and its aftermath as it affects three friends whose sympathies lie on different sides of the conflict.

Another American who writes about a return to her origins is Cristina Garcia who wrote Dreaming in Cuban twenty-five years ago. Of the three novels I brought to Cuba on a recent trip, this is the one that most clearly defined the struggle of the Cubans and the Florida refugees through the first decades after the revolution. Employing the perspectives of three generations of women, it deftly illustrates the conditions of patriotism interpreted through the daily rituals of living. I also brought Alejo Carpentier’s The Chase, a book that reads like a Russian psychological thriller mixed with Kafka’s absurd take on the modern world, revolving around a performance of Beethoven’s Eroica. There are statues of Carpentier in Havana – he was a hero of the revolution, but this book illustrates the multiple sides of every conflict, told on the run. Islands in the Stream is Hemingway’s novel of life around Havana during World War II and leading up to the revolution. It’s a story of fishing, painting, drinking, and family, published posthumously, no doubt autobiographical. Fine words by one of the best, but it is about a different island, the colonial world, no longer in existence. The three books combined helped me put what I witnessed in Havana in perspective, more so than the guidebook I carried.

After reading What is the What a few years ago, I keep Dave Eggers on my antennae. I picked up Heroes of the Frontier and had great fun reading it, as he manages to get inside the head of his protagonist, a dentist who loses her practice to a scam of malpractice and her husband to a younger woman, who leases a camper and runs off with her kids to Alaska, who maintains that things will work out, despite the fact that she constantly doubts the people around her, thinking her husband and the authorities are on her tail. It’s a great road trip and reading romp, as she is prone to the same paranoia many of us face on a routine basis. Doubts and glimmers of hope, and fine heroes.

Colson Whitehead wrote one of the big books of the year, The Underground Railroad, and although I wasn’t initially impressed, by the time I was halfway through it, the author had got me with a slave narrative that travels through different regions via a magical railroad. The focus on language and landscape, and Cora’s constant escapes allows the railroad to transport the reader as well. A good read, and hopefully a memorable series from the director of Moonlight.